So the New Green Deal is already getting a lot of attention and push-back – both to the good. It’s at least bold enough in some ways to get noticed, if not bold enough in others. For so long, the conversation has been muted by a sense of futility that is quite self-indulgent. Nonetheless…

Not far enough? Correct:

But the Green New Deal has a big blind spot: It doesn’t address the places Americans live. And our physical geography—where we sleep, work, shop, worship, and send our kids to play, and how we move between those places—is more foundational to a green, fair future than just about anything else. The proposal encapsulates the liberal delusion on climate change: that technology and spending can spare us the hard work of reform.

The Environment

America is a nation of sprawl. More Americans live in suburbs than in cities, and the suburbs that we build are not the gridded, neighborly Mayberrys of our imagination. Rather, the places in which we live are generally dispersed, inefficient, and impossible to navigate without a car. Dead-ending cul-de-sacs and the divided highways that connect them are such deeply engrained parts of the American landscape that it’s easy to forget they were, themselves, the fruits of a massive federal investment program.

Sprawl is made possible by highways. This is expensive—in 2015, the Victoria Transport Policy Institute estimated that sprawl costs America more than $1 trillion a year in reduced business activity, environmental damage, consumer expenses, and other costs. Leaving aside the emissions from the 1.1 billion trips Americans take per day (87 percent of which are taken in personal vehicles), spreading everything out has eaten up an enormous amount of natural land.

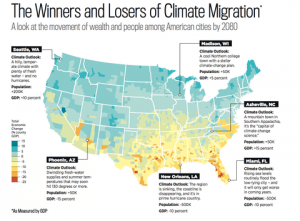

Tell them what they could win, Jonny:

But the good news is that if we do account for land use, we will get much closer to a safe, sustainable, and resilient future. And even though widespread adoption of EVs is still decades away, reforms to our built environment can begin right now. In short, we can fix this. We build more than 1 million new homes a year—we just need to put them in the right places.*

Unsprawling America isn’t as hard as it sounds, because America is suffering from a critical, once-in-a-lifetime housing shortage. The National Low Income Housing Coalition reported last year that the U.S. has a national deficit of more than 7.2 million affordable and available rental homes for families most in need. Of course, if we build those homes in transit-accessible places, we can save their occupants time and money. But the scale of housing demand at this moment is such that we could build them in car-centric suburbs, too, and provide a human density that would not just support transit but also reduce the need to travel as shops, jobs, and schools crop up within walking distance.

Walking distance needs to become an old/new catch phrase. Also, as another Slate article proclaims, plane trips CAN be replaced by train trips. Not LA to NYC, and not even NYC to Chicago. But most trips under 500 miles and all trips under 300 miles could be taken out of the equation with an updated modest-speed rail system. 100 miles per hour cuts what is a four-hour drive to three (math!), plus airports are never in city centers – you always have to drive in. Bump up the speed to even 150 mph and, well, a 2 hour trip. Math!

Image via Alon Levy on the twitters.