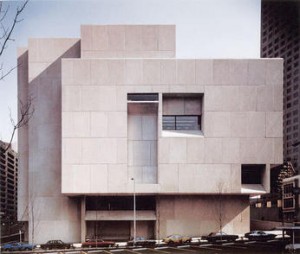

by any other name. A friend of mine wrote this article about another one of those, shall we say, constructive dilemmas: build a new-fangled structure in a newish city, wait thirty years until they want something else cutting edge (ouch!) and new, then watch as they decide what to do about the old building. In this case the old building is the final structure of Modernist master Marcel Breuer. Take it, JL:

Breuer’s design sits closely surrounded by other buildings where Peachtree Street, a principal artery, touches a remaining patch of narrow, 19th-century street grid, about a half mile southeast of the proposed Centennial Olympic Park site. If the building could be viewed whole, from a greater distance, its sculptural power might be more affecting. As it is, Pitts and others don’t get it. “From a design point of view, it probably means a lot to those in the field, but for the average citizen who sees it, it’s just not there,” he says. “It’s dark, it’s not friendly, it’s not inviting.” Isabelle Hyman, a Breuer scholar at New York University, acknowledges that “the concrete architecture of that period is disdained right now. It’s massive, heavy, bulky, weighty, and it’s not appreciated.” Still, she insists, “You just don’t get rid of a good building by a good architect because it’s out of style.” Pitts would prefer a building with of-the-moment transparency. “I envision glass and color and water and openness,” he says. But can a shiny new building attract patrons to the library, and visitors to Atlanta?

So… there’s a thread here, connecting what they’re contemplating doing with this building and what has saddled them with an urban landscape largely indistinguishable from that of Dallas or Indianapolis or Phoenix. Can anyone guess what it is?

For another thing, why not let the building stand as a marker for the question of why we designed and built structures like this once upon a time? Could be instructive.

And what do you know, there even could be a fiscal upside to preserving the structure, beyond its architectural merits.

Jon Buono, a preservation architect, makes a compelling pragmatic argument for saving the building. “I’m clearly interested in the artistic and cultural value of the library,” he says. “But as a civic booster, I’m even more concerned with recognizing the financial and material value of that public investment.” He calculates that the energy embodied in the library and required for its demolition equals a year’s electricity consumption by some 4,000 households.

Hmm. Preserve cultural heritage. Save the city some money. Conserve a non-trivial amount of energy. Does this compute? Or is it a plan written in a book, shelved in a library that’s become obsolete?