The 2010 Fields Medals were carelessly handed out yesterday, in an utterly random fashion – I think they drew the names out a hat. The only requirements for the controversial prize is that winners are under forty years old and demonstrate some unquestionably innovative mathematical calculation that fundamentally alters our understanding of the world.

Take this winner, for instance, Cedric Villani of France, who calculated the rate at which entropy is increasing – there seems to be some sort of throttle on the rate at which the world is falling apart.

Cedric Villani works in several areas of mathematical physics, and particularly in the rigorous theory of continuum mechanics equations such as the Boltzmann equation.

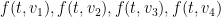

Imagine a gas consisting of a large number of particles traveling at various velocities. To begin with, let us take a ridiculously oversimplified discrete model and suppose that there are only four distinct velocities that the particles can be in, namely  , and

, and  . Let us also make the homogeneity assumption that the distribution of velocities of the gas is independent of the position; then the distribution of the gas at any given time

. Let us also make the homogeneity assumption that the distribution of velocities of the gas is independent of the position; then the distribution of the gas at any given time  can then be described by four densities

can then be described by four densities  adding up to

adding up to  , which describe the proportion of the gas that is currently traveling at velocities

, which describe the proportion of the gas that is currently traveling at velocities  , etc..

, etc..

If there were no collisions between the particles that could transfer velocity from one particle to another, then all the quantities  would be constant in time:

would be constant in time:  . But suppose that there is a collision reaction that can take two particles traveling at velocities

. But suppose that there is a collision reaction that can take two particles traveling at velocities  and change their velocities to

and change their velocities to  , or vice versa, and that no other collision reactions are possible. Making the heuristic assumption that different particles are distributed more or less independently in space for the purposes of computing the rate of collision, the rate at which the former type of collision occurs will be proportional to

, or vice versa, and that no other collision reactions are possible. Making the heuristic assumption that different particles are distributed more or less independently in space for the purposes of computing the rate of collision, the rate at which the former type of collision occurs will be proportional to  , while the rate at which the latter type of collision occurs is proportional to

, while the rate at which the latter type of collision occurs is proportional to  . This leads to equations of motion such as

. This leads to equations of motion such as

for some rate constant  , and similarly for

, and similarly for  ,

,  , and

, and  . It is interesting to note that even in this simplified model, we see the emergence of an “arrow of time”: the rate of a collision is determined by the density of the initialvelocities rather than the final ones, and so the system is not time reversible, despite being a statistical limit of a time-reversible collision from the velocities

. It is interesting to note that even in this simplified model, we see the emergence of an “arrow of time”: the rate of a collision is determined by the density of the initialvelocities rather than the final ones, and so the system is not time reversible, despite being a statistical limit of a time-reversible collision from the velocities  to

to  and vice versa.

and vice versa.

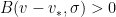

To take a less ridiculously oversimplified model, now suppose that particles can take a continuum of velocities, but we still make the homogeneity assumption the velocity distribution is still independent of position, so that the state is now described by a density function  , with

, with  now ranging continuously over

now ranging continuously over  . There are now a continuum of possible collisions, in which two particles of initial velocity

. There are now a continuum of possible collisions, in which two particles of initial velocity  (say) collide and emerge with velocities

(say) collide and emerge with velocities  . If we assume purely elastic collisions between particles of identical mass

. If we assume purely elastic collisions between particles of identical mass  , then we have the law of conservation of momentum

, then we have the law of conservation of momentum

and conservation of energy

some simple Euclidean geometry shows that the pre-collision velocities  must be related to the post-collision velocities

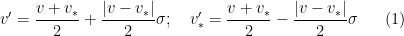

must be related to the post-collision velocities  by the formulae

by the formulae

for some unit vector  . Thus a collision can be completely described by the post-collision velocities

. Thus a collision can be completely described by the post-collision velocities  and the pre-collision direction vector

and the pre-collision direction vector  ; assuming Galilean invariance, the physical features of this collision can in fact be described just using the relative post-collision velocity

; assuming Galilean invariance, the physical features of this collision can in fact be described just using the relative post-collision velocity  and the pre-collision direction vector

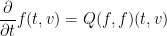

and the pre-collision direction vector  . Using the same independence heuristics used in the four velocities model, we are then led to the equation of motion

. Using the same independence heuristics used in the four velocities model, we are then led to the equation of motion

where  is the quadratic expression

is the quadratic expression

for some Boltzmann collision kernel  , which depends on the physical nature of the hard spheres, and needs to be specified as part of the dynamics. Here of course

, which depends on the physical nature of the hard spheres, and needs to be specified as part of the dynamics. Here of course  are given by (1).

are given by (1).

If one now allows the velocity distribution to depend on position  in a domain

in a domain , so that the density function is now

, so that the density function is now  , then one has to combine the above equation with a transport equation, leading to the Boltzmann equation

, then one has to combine the above equation with a transport equation, leading to the Boltzmann equation

together with some boundary conditions on the spatial boundary  that will not be discussed here.

that will not be discussed here.

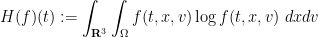

One of the most fundamental facts about this equation is the Boltzmann H theorem, which asserts that (given sufficient regularity and integrability hypotheses on  , and reasonable boundary conditions), the

, and reasonable boundary conditions), the  -functional

-functional

is non-increasing in time, with equality if and only if the density function  is Gaussian in

is Gaussian in  at each position

at each position  (but where the mass, mean and variance of the Gaussian distribution being allowed to vary in

(but where the mass, mean and variance of the Gaussian distribution being allowed to vary in  ). Such distributions are known asMaxwellian distributions.

). Such distributions are known asMaxwellian distributions.

From a physical perspective,  is the negative of the entropy of the system, so the H theorem is a manifestation of the second law of thermodynamics, which asserts that the entropy of a system is non-decreasing in time, thus clearly demonstrating the “arrow of time” mentioned earlier.

is the negative of the entropy of the system, so the H theorem is a manifestation of the second law of thermodynamics, which asserts that the entropy of a system is non-decreasing in time, thus clearly demonstrating the “arrow of time” mentioned earlier.

There are considerable technical issues in ensuring that the derivation of the H theorem is actually rigorous for reasonable regularity hypotheses on  (and on

(and on  ), in large part due to the delicate and somewhat singular nature of “grazing collisions” when the pre-collision and post-collision velocities are very close to each other. Important work was done by Villani and his co-authors on resolving this issue, but this is not the result I want to focus on here. Instead, I want to discuss the long-time behaviour of the Boltzmann equation.

), in large part due to the delicate and somewhat singular nature of “grazing collisions” when the pre-collision and post-collision velocities are very close to each other. Important work was done by Villani and his co-authors on resolving this issue, but this is not the result I want to focus on here. Instead, I want to discuss the long-time behaviour of the Boltzmann equation.

As the  functional always decreases until a Maxwellian distribution is attained, it is then reasonable to conjecture that the density function

functional always decreases until a Maxwellian distribution is attained, it is then reasonable to conjecture that the density function  must converge (in some suitable topology) to a Maxwellian distribution. Furthermore, even though the

must converge (in some suitable topology) to a Maxwellian distribution. Furthermore, even though the theorem allows the Maxwellian distribution to be non-homogeneous in space, the transportation aspects of the Boltzmann equation should serve to homogenise the spatial behaviour, so that the limiting distribution should in fact be a homogeneous Maxwellian. In a remarkable 72-page tour de force, Desvilletes and Villani showed that (under some strong regularity assumptions), this was indeed the case, and furthermore the convergence to the Maxwellian distribution was quite fast, faster than any polynomial rate of decay in fact. Remarkably, this was alarge data result, requiring no perturbative hypotheses on the initial distribution (although a fair amount of regularity was needed). As is usual in PDE, large data results are considerably more difficult due to the lack of perturbative techniques that are initially available; instead, one has to primarily rely on such tools as conservation laws and monotonicity formulae. One of the main tools used here is a quantitative version of the H theorem (also obtained by Villani), but this is not enough; the quantitative bounds on entropy production given by the H theorem involve quantities other than the entropy, for which further equations of motion (or more precisely, differential inequalities on their rate of change) must be found, by means of various inequalities from harmonic analysis and information theory. This ultimately leads to a finite-dimensional system of ordinary differential inequalities that control all the key quantities of interest, which must then be solved to obtain the required convergence.

theorem allows the Maxwellian distribution to be non-homogeneous in space, the transportation aspects of the Boltzmann equation should serve to homogenise the spatial behaviour, so that the limiting distribution should in fact be a homogeneous Maxwellian. In a remarkable 72-page tour de force, Desvilletes and Villani showed that (under some strong regularity assumptions), this was indeed the case, and furthermore the convergence to the Maxwellian distribution was quite fast, faster than any polynomial rate of decay in fact. Remarkably, this was alarge data result, requiring no perturbative hypotheses on the initial distribution (although a fair amount of regularity was needed). As is usual in PDE, large data results are considerably more difficult due to the lack of perturbative techniques that are initially available; instead, one has to primarily rely on such tools as conservation laws and monotonicity formulae. One of the main tools used here is a quantitative version of the H theorem (also obtained by Villani), but this is not enough; the quantitative bounds on entropy production given by the H theorem involve quantities other than the entropy, for which further equations of motion (or more precisely, differential inequalities on their rate of change) must be found, by means of various inequalities from harmonic analysis and information theory. This ultimately leads to a finite-dimensional system of ordinary differential inequalities that control all the key quantities of interest, which must then be solved to obtain the required convergence.

Gee… talk about your run-of-the-mill finite-dimensional systems of ordinary differential inequalities. I mean, tell us something we don’t know, Monsieur medal winner.