Take him back to Tulsa, indeed.

Raise your hand if you thought the original Juneteenth date was a coincidence. Wow. No Takers.

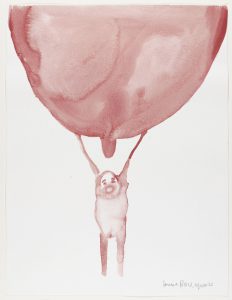

The absurdism of this fascist performance art expresses the thin smallness of this entire four-year escapade of MAGA authoritarianism led by a needy, under-educated man-child. We can be grateful in many ways for the incurious incompetence on continual display. People joke about slogans that sounded better in the original German, but the sheer unstudied pettiness of it makes the earlier epoch seem practically elegant by comparison:

ONE HUNDRED years ago, on the early morning of March 23, 1919, a small crowd gathered in the Piazza San Sepolcro in Milan, a few blocks west of the Duomo. Many had arrived from other cities the night before, drawn to hear a charismatic young journalist, former socialist, and recent war veteran, who—with a vigor that would mark his discourses for two decades to come—duly trumpeted the ambitions of a new political movement. As a self-declared “anti-party,” Benito Mussolini’s Fasci Italiani di combattimento (Italian Combat Fasci or, simply, Fascists)1 aimed to yoke growing social unrest to an unabashed nationalism, freshly stoked by the country’s victory in World War I alongside the Entente powers (Britain, France, and Russia). Dubbed the Sansepolcristi for their presence at this fateful first meeting, the so-called Fascists of the first hour counted among their number syndicalists and ex-soldiers, even a few women and Italian Jews, as well as artists and writers such as the painters Achille Funi and Primo Conti and the Futurist poet-impresario, F.T. Marinetti.

For the preceding ten years, Marinetti’s Futurists had upended Italian culture in every imaginable domain, from painting and poetry to clothing, music, architecture, photography, and theater. A political phenomenon as much as an aesthetic crusade, Futurism lent Fascism much of its early ideological impetus: anti-Communist and anti-clerical, interventionist and irredentist, hostile to academic pedantry and cultural patrimony alike.

Substitute ‘reality TV’ for ‘Futurists’ in the above for a more accurate, recent rendering.

Image: author photo, Rome.

:

: