What is the concept of afford, and does it work both ways? The question is not whether it can work two ways, but for the concept to be meaningful at all, it has to be fully operational with regard to meaning.

We’re not just deciding what to spend money on — wait, yes we are! In so doing, any action must be considered in the context of its opportunity cost, and with further unpacking of the consequences of not spending money on certain things, the consequences this decision assures.

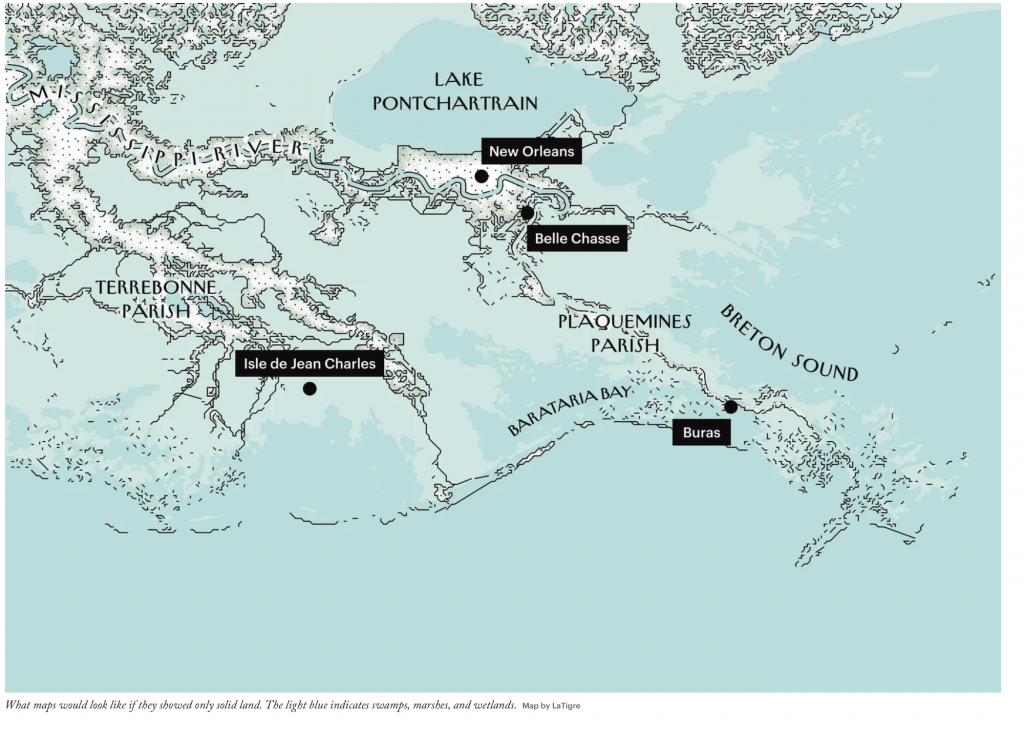

For instance, Mr. Sarda said, it’s relatively straightforward for businesses to calculate the potential costs from an increase in taxes designed to curb emissions of carbon dioxide, a major greenhouse gas that contributes to global warming. Indeed, this is one of the most common climate-related risks that companies now disclose. But it’s trickier to take scientific reports about rising temperatures and weather extremes and say what those broad trends might mean for specific companies in specific locations.

Previous studies, based on computer climate modeling, have estimated that the risks of global warming, if left unmanaged, could cost the world’s financial sector between $1.7 trillion to $24.2 trillion in net present value terms. A recent analysis published in the journal Nature Climate Change warned that companies are reporting on these risks only “sporadically and inconsistently” and often take a narrow view of the dangers that may lie ahead.

The financial context of whether or not to do something – can we pay for doing the thing – extends in validity only as far as this framing is reversed: can we afford not to do something.

That is, the so-called cost of addressing climate change – or homelessness – large problems who’s answers supposedly involved gross amounts of expenditure that could be determined to be too large must also be considered in their reverse outlines. What is the cost of doing nothing? Is this affordable? Here the concept actually has meaning and may provide a constructive way forward.

But if we decide not to spend money on ameliorating climate change expressly because the measures are deemed prohibitively expensive, and yet the broad effects of climate change prove to be even more expensive than the proposed steps, then the affordability argument is invalid, if not disingenuous. While it may be the case that some consequences are unknowable in advance, that truth equally invalidates the affordability argument in advance. If it can’t be known whether a step would be worth it, it likewise cannot be known whether ignoring a step might be a price too high.

TL;Dr – Decisions made to ignore the effects of climate change must be taken for a reason other than the affordability argument.