The previous three Supreme Court Justice nominees – Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, and Barret – knowingly lied in their confirmation hearings.

From an archived Artforum preview:

Through October 15, New York’s Museum of Sex hosts Barcelona-based artist Laia Abril’s exhibition “On Abortion: And the Repercussions of Lack of Access.” One chapter of her larger project “A History of Misogyny,” “On Abortion” chronicles obstacles to reproductive choice in across the world. Abril employs a documentary mode common to conceptual art, drawing on the testimonies of individuals who were denied care. She pairs black-and-white photographic portraits of her subjects with typed statements and evidentiary images of their struggles, such as maps of their travels to neighboring countries for health care and photos of shadowy waiting rooms and plum pits (as one woman describes the size of her fetus). The subjects include Françoise, a septuagenarian Frenchwoman who performed five thousand clandestine abortions from the ’70s to the ’90s, to three Chinese women—identified by their initials ZWF, FJ, and GYL—whose abortions and sterilizations were forced upon them. Abril also uses the photographic grid format to depict the desperate measures people have taken to end pregnancy throughout history, from herbal mixtures to the coat hanger method. Alongside Abril’s work, curator Lissa Rivera exhibits birth-control artifacts from the Museum of Sex holdings and gynecological tools from the Burns Archive, a private collection in Manhattan devoted to medical photography and objects from the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The sober nature of Abril’s exhibition sharply contrasts with the spectacular format of the MoSex shows directly above and below hers—on webcam models and fin de siècle stag films, respectively. Still, on a recent busy Friday night at the museum, “On Abortion” invited quiet contemplation from a busy crowd.

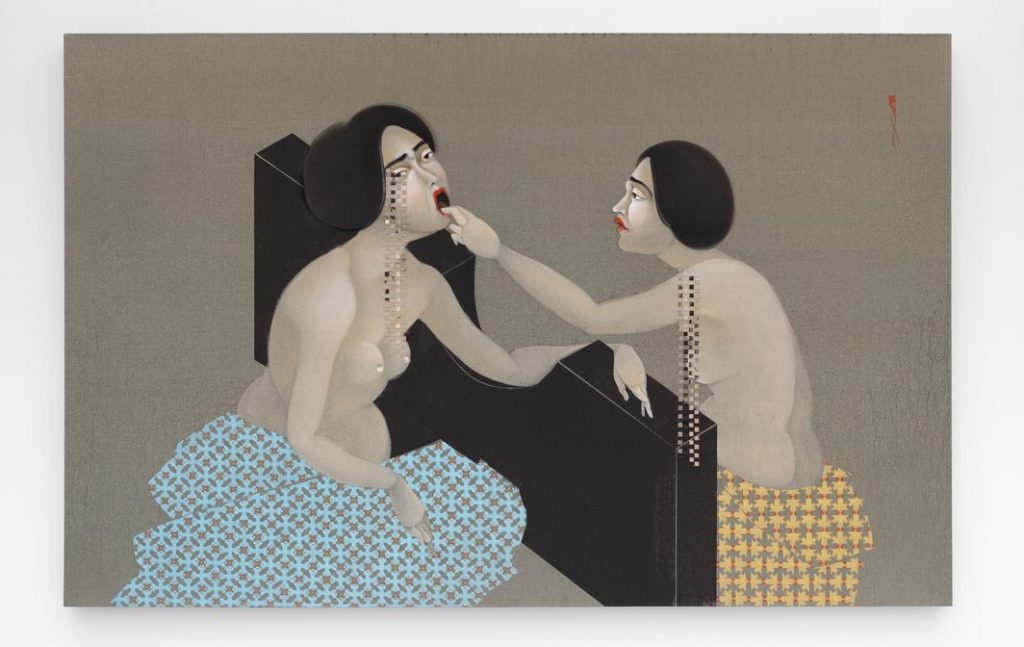

In January and February, the two-part show “Abortion Is Normal” was mounted at the downtown galleries Eva Presenhuber and Arsenal Contemporary Art. Conceived as a fundraiser for Downtown for Democracy, a liberal super PAC, the show donated its proceeds to Planned Parenthood and efforts to support voter education on reproductive rights. Curated by Project for Empty Space Newark cofounders Rebecca Pauline Jampol and Jasmine Wahi and co-organized by Marilyn Minter, Gina Nanni, Laurie Simmons, and Sandy Tait, the show brought together over fifty diverse artists—several with blue-chip appeal, like Barbara Kruger and Cindy Sherman. While the title polemically defined reproductive rights as normal healthcare, the works on view approached bodily and sexual autonomy in various ways, oscillating in attitude between anger, celebration, and grief. Carrie Mae Weems’s photograph The Broken, See Duchamp, 2012–16, depicts the artist in a spread-eagled posture reminiscent of Etant donnés; Hayv Kahraman’s paintings of fair-skinned, dark-haired women, punctuated with woven bits of canvas, suggest the fracturing and mending potentials of art in the wake of traumas related to sexual violation and migration. Jane Kaplowitz’s painted portraits of Ruth Bader Ginsburg lionize the Supreme Court Justice, while Jon Kessler’s multimedia collage Birmingham, 2019, mourns the victims of the 1998 bombing of an Alabama abortion clinic by the terrorist Eric Rudolph.

Image: Hayv Kahraman, Barricade 1, 2018, oil on linen, 50 x 78 x 3”.

Like smartphones teach us to be dumb – to not know things, to not be able to find our way except by using the device – we are also learning how to forget the past. Or how to remember it inaccurately, disconnected from the forks in the road where our path darkened and we lost something irretrievable, something we did not make nor deserve but that came from us and birthed us, was us, the best and the worst, that pushed us in the right direction because we were scared to go on our own until we learned we could pull ourselves there if we could just join enough hands.

Like smartphones teach us to be dumb – to not know things, to not be able to find our way except by using the device – we are also learning how to forget the past. Or how to remember it inaccurately, disconnected from the forks in the road where our path darkened and we lost something irretrievable, something we did not make nor deserve but that came from us and birthed us, was us, the best and the worst, that pushed us in the right direction because we were scared to go on our own until we learned we could pull ourselves there if we could just join enough hands.