The Crisis Theme that seems to be the default, unchangeable background of everything these days can be exhausting. None of us seems to know how to handle social media – is it for self-promotion? sharing opinions? business? the fck is a status update? connecting instead of conversing – beyond obsessive attention to it or turning it off completely. That the tools have been created to make other people rich appears to be a mere byproduct, but is it? Do I need to read an article on it that my friends agree with to believe that? Every news item from the Dunce-in-chief to climate change to what’s wrong with the Democratic party to health care to guns hermetically seals us in a state of doubtful knowing. And like quicksand, if you try to get out of it too desperately, you’re only pulled back all the more. For those who insist on creating, it can be be double-trouble: your battle is not to react against but still ‘do something.’ What does that mean?

Friend of the blog Jed Perl lays out in an inadvertent cautionary tale in this Rauschenberg review, The Confidence Man of American Art:

It was as a genre-buster—an artist who crossed boundaries and cross-pollinated disciplines—that Rauschenberg was embraced in the 1960s. More than fifty years later, there are more and more artists who seem to believe, as he apparently did, that art is unbounded. The only difference is that our contemporaries—figures such as Jeff Koons, Isa Genzken, and Matthew Day Jackson—have traded his whatever-you-want for an even more open-ended and blunt whatever. A creative spirit, according to the argument that Rauschenberg did so much to advance, need not be merely a painter, a photographer, a stage designer, a printmaker, a moviemaker, a collagist, an assemblagist, a writer, an actor, a musician, or a dancer. An artist can be any or all of these things, and even many of them simultaneously. The old artisanal model of the artist—the artist whose genius is grounded in the demands of a particular craft—is replaced by the artist who is often not only figuratively but also literally without portfolio, a creative personality-at-large in the arts.

One can argue that there are historical precedents for this view. Picasso enriched both his painting and his sculpture by working back and forth between the two disciplines. And the work that Picasso did in the theater certainly precipitated significant shifts in his painting.

Just so, and there is much more. And I do not come to praise Rauschenberg or to bury him. One point can be that, for better or worse, he imagined himself and what he was doing. Sure he was affected by his culture and the times in which he lived. But Jed is correct – the question is where the question (whatever it is) takes the artist. If it runs you back into into the insufferable quandary of boredom or futility, it wasn’t the right question. We can work our way through this time, as others have other times, but not by taking it on directly. Okay maybe, if you’re Zola. But you’re not. So don’t do that at all. Ignore it? Abdication is consent. Also – nothing will change. That’s one reason to like the ‘confidence man’ citizen’s arrest of Rauschenberg. It’s a hefty charge. But that’s okay – you don’t need to [first] accept any of the givens about anyone or thing in order to get somewhere. And this is not about progress, anyway. It’s about getting to all some of that other space, all around you, that seems inaccessible. That’s what can be frustrating – and it’s not even true. It’s just a thing someone has created and you’ve allowed to be in your way, that you need to [yes] use your discipline to think beyond. And [yes] to make something.

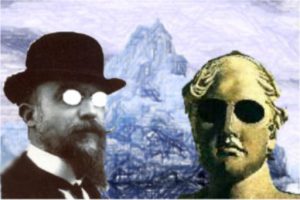

Image: Portrait of Apollinaire as a Premonition, by Giorgio de Chiricio, 1914