You want to believe the reports or your lying eyes, it’s getting more and more difficult to hydrate climate denial. Yes, people are still getting rich doing so, with full employment for lobbyists who still help companies muddle the puddles. But that’s basically what they are now and we are full on in our incoherence meltdown. Slow moving isn’t slow enough for the summer news cycle, and though they are always looks for way to spice things up, there’s not a lot of chase left to cut to:

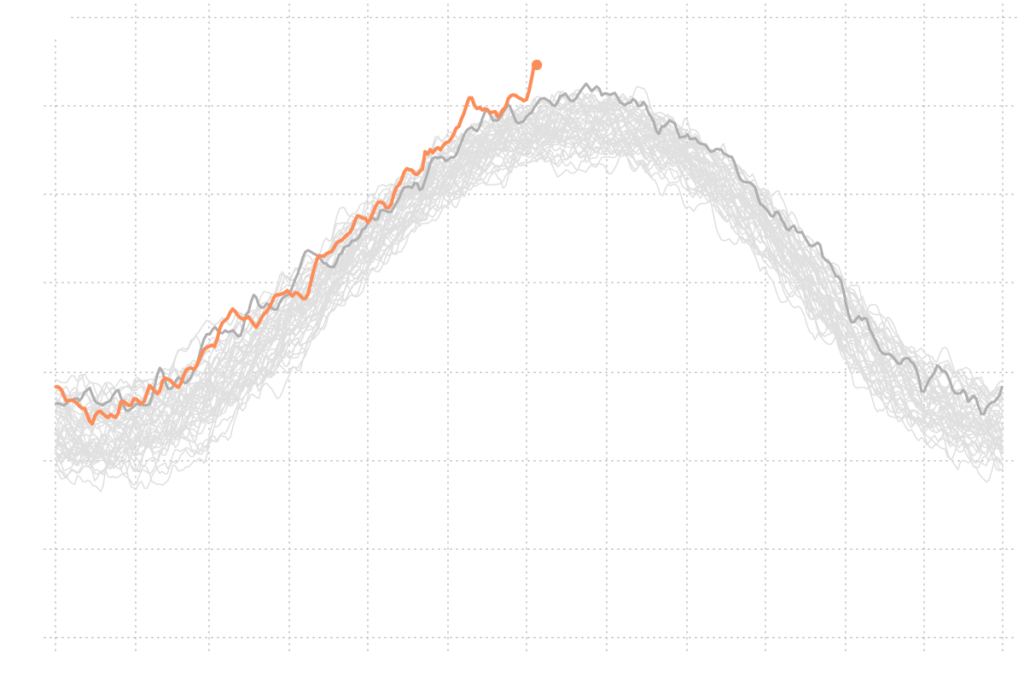

The past three days were quite likely the hottest in Earth’s modern history, scientists said on Thursday, as an astonishing surge of heat across the globe continued to shatter temperature records from North America to Antarctica.

The spike comes as forecasters warn that the Earth could be entering a multiyear period of exceptional warmth driven by two main factors: continued emissions of heat-trapping gases, mainly caused by humans burning oil, gas and coal; and the return of El Niño, a cyclical weather pattern.

…

The sharp jump in temperatures has unsettled even those scientists who have been tracking climate change.

“It’s so far out of line of what’s been observed that it’s hard to wrap your head around,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior research scientist at the University of Miami. “It doesn’t seem real.”

On Tuesday, global average temperatures climbed to 62.6 degrees Fahrenheit, or 17 Celsius, making it the hottest day Earth has experienced since at least 1940, when records began, and very likely before that, according to an analysis by the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service.

Up next: stuck weather patterns, wavy flow, amplified troughs and ridges – and that’s just for the mid-latitudes. Get wise to the flimflammery.

Image: By Elena Shao/The New York Times