Sure, it will bond to any old thing – just a fun-loving, good time chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. Call anytime.

And though carbon is not magnetic, it does attract kooks. Okay, no harm there, chacun à son goût and all that. We’re not all kooks. We even devise ways around it – solar, wind, other means of generating that dirty dirty electricity that we enjoy so much. And you won’t believe what happens next:

This scene from the village council meeting in June helps to explain why opponents of three solar projects proposed in Pickaway County, Ohio, can say they have the support of nearly every local elected official. It shows how a committed group of local residents have dominated the debate by packing county, village and township meetings, and making their displeasure known if officials don’t fall into line.

The prevailing emotion is fear, whether it’s fear of the solar projects—or fear of upsetting the people who oppose the projects.

And the local fight has broad implications. The world needs to increase its reliance on renewable energy, an essential part of avoiding the most destructive effects of climate change. Local opposition shows some of the disconnect between global needs and the concerns of some of the people who don’t want to live next door to wind and solar projects.

It’s a little beyond as well as different from traditional NIMBYism, though also quite similar in several ways, as the locals literally don’t want to be living next to utility-scale solar. They don’t want to see it and they don’t want to hear it. Though it’s not a discussion about energy and how they get it at all. “Just leave us alone,” they might say, then step back inside and to watch the ballgame. And there’s the rub.

Whether we blame them for not wanting to connect their own usage of dirty energy to their passions for their freedom not to see it, or blame the local school district that benefits from the increase in tax revenue for not being more vocal in their support for the solar projects, the moment and the conflicts should be noted. The difficulty of telling nominally self-governing people what to do when their own understanding of any right thing is itself in conflict with abstractions like freedom is certainly one of the more devious tricks slutty carbon has played on us.

It’s sort of a next-level struggle with renewables that has nothing to do with energy – because focused on how we’re gonna watch the game or dry the clothes, or even live that far from the grocery store [don’t get me started], the question changes entirely. At least the NIMBYism is familiar.

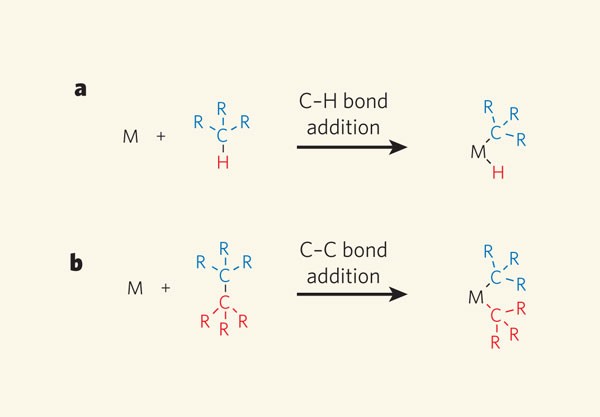

Image: Carbon–carbon bonds get a break | Nature