Courtesy of the Review – subscribe and invest in media, whatever it is you read. The NYRB works for me – a review/discussion of two new books about the history of Silicon Valley. You’ll never guess the rationale behind the creation of Stanford the University. Wait – yes, sure you will:

Stanford wanted to breed stronger horses, faster. There was a clear business rationale: at the time, horses were essential for transportation, agriculture, and war. He proposed transforming horse production in the same way that the production of so many other commodities was being transformed during the second industrial revolution: with modern techniques and technologies. This modernizing mentality, as Harris demonstrates, was visible everywhere in California, which has been “a high-technology zone from the beginning of Anglo colonization.” Because there were never enough wage workers, the state relied particularly heavily on “labor-saving machinery” in agriculture, which by the 1860s had overtaken mining as its main economic driver.

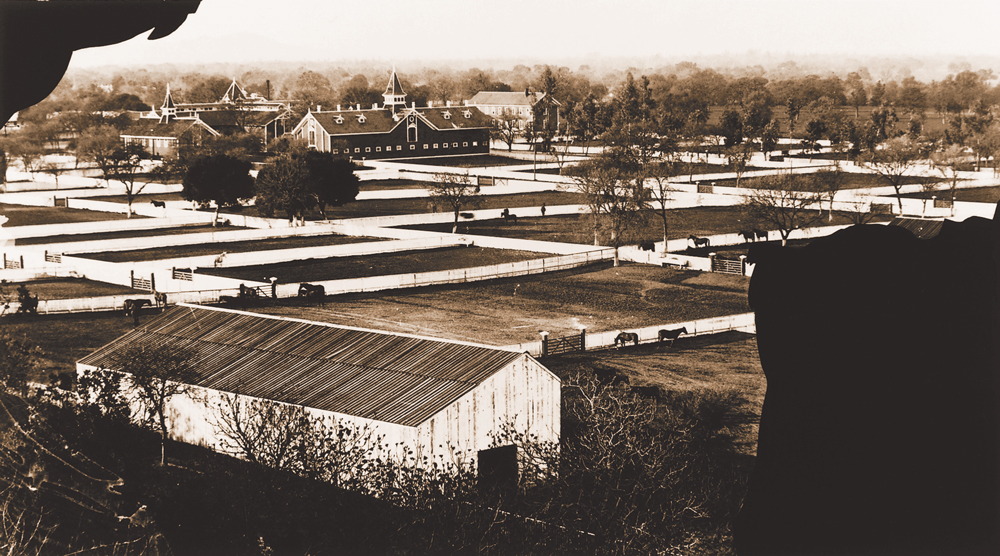

The Palo Alto Stock Farm turned out to be a big success. The principal innovation was the Palo Alto System, which involved teaching horses to trot when they were young. That way, Stanford and his operatives could identify the promising ones early, train them intensively, and then use them as studs to produce more promising colts, thereby transmitting talent via superior genes. “Instead of optimizing for adult speed, they optimized for visible potential,” Harris writes.

The Palo Alto System didn’t stop with horses. It became the guiding philosophy of the university that Stanford carved out of his estate in 1885. Harris focuses in particular on David Starr Jordan, the university’s first president, whom Harris credits with bringing the Palo Alto System “out of the barn and into the classroom.” Like many self-styled modernizers of the period, Jordan loved eugenics. Under his direction, Harris argues, “the small, young university became a national center for controlled evolution.” Young white people with potential would be identified and intensively trained, in the hope of staving off racial decay.

One of the features of the Palo Alto System as it applied to horses was an obsession with quantification. As the system migrated to humans, this quantifying impulse turned toward intelligence testing. Lewis Terman, a psychologist who joined Stanford University in 1910, helped popularize the notion that intelligence could be expressed in a single number, such as an IQ score. He was especially interested in high-IQ children. “Budding geniuses needed to be identified and elevated,” Harris writes, “while young degenerates needed to be corralled where they couldn’t dilute the national race or turn their underachievement into social problems.”

And… once again, here we are. Racism continues to be our fundamental foundation, regardless of region. There is no realm in which the wealthy can’t channel their profits into their hatred. Great job, everybody.

Image: Palo Alto Stock Farm (Photos: Stanford Archives)