Since everything seems to be All Russia, All the Time, I’ve been thinking about Konstantin Levin, the most interesting character from Anna Karenina, and relatedly D.H. Lawrence, who did not care much for what Tolstoy was saying with Levin. But for some other probably suspicious reason was led back to Turgenev and Knock Knock Knock:

Since everything seems to be All Russia, All the Time, I’ve been thinking about Konstantin Levin, the most interesting character from Anna Karenina, and relatedly D.H. Lawrence, who did not care much for what Tolstoy was saying with Levin. But for some other probably suspicious reason was led back to Turgenev and Knock Knock Knock:

Two incidents that marked the first steps in his career did a great

deal to strengthen his “fatal” reputation. On the very first day after

receiving his commission–about the middle of March–he was walking

with other newly promoted officers in full dress uniform along the

embankment. The spring had come early that year, the Neva was melting;

the bigger blocks of ice had gone but the whole river was choked up

with a dense mass of thawing icicles. The young men were talking and

laughing … suddenly one of them stopped: he saw a little dog some

twenty paces from the bank on the slowly moving surface of the river.

Perched on a projecting piece of ice it was whining and trembling all

over. “It will be drowned,” said the officer through his teeth. The

dog was slowly being carried past one of the sloping gangways that led

down to the river. All at once Tyeglev without saying a word ran down

this gangway and over the thin ice, sinking in and leaping out again,

reached the dog, seized it by the scruff of the neck and getting

safely back to the bank, put it down on the pavement. The danger to

which Tyeglev had exposed himself was so great, his action was so

unexpected, that his companions were dumbfoundered–and only spoke all

at once, when he had called a cab to drive home: his uniform was wet

all over. In response to their exclamations, Tyeglev replied coolly

that there was no escaping one’s destiny–and told the cabman to drive

on.“You might at least take the dog with you as a souvenir,” cried one of

the officers. But Tyeglev merely waved his hand, and his comrades

looked at each other in silent amazement.The second incident occurred a few days later, at a card party at the

battery commander’s. Tyeglev sat in the corner and took no part in the

play. “Oh, if only I had a grandmother to tell me beforehand what

cards will win, as in Pushkin’s _Queen of Spades_,” cried a

lieutenant whose losses had nearly reached three thousand. Tyeglev

approached the table in silence, took up a pack, cut it, and saying

“the six of diamonds,” turned the pack up: the six of diamonds was the

bottom card. “The ace of clubs!” he said and cut again: the bottom

card turned out to be the ace of clubs. “The king of diamonds!” he

said for the third time in an angry whisper through his clenched

teeth–and he was right the third time, too … and he suddenly turned

crimson. He probably had not expected it himself. “A capital trick! Do

it again,” observed the commanding officer of the battery. “I don’t go

in for tricks,” Tyeglev answered drily and walked into the other room.

How it happened that he guessed the card right, I can’t pretend to

explain: but I saw it with my own eyes. Many of the players present

tried to do the same–and not one of them succeeded: one or two did

guess _one_ card but never two in succession. And Tyeglev had

guessed three! This incident strengthened still further his reputation

as a mysterious, fatal character. It has often occurred to me since

that if he had not succeeded in the trick with the cards, there is no

knowing what turn it would have taken and how he would have looked at

himself; but this unexpected success clinched the matter.

Honi soit, as Lev wrote.

In early September 2008, I drove down to Charleston to visit a cousin who had recently suffered a terrible accident. Throughout the drive I listened to extended public radio reports on an evolving calamity: the collapse of Lehman Brothers financial services firm. The horror that the government was going to allow such a large firm to go under was decorated with the baroque gadgetry of terms that would become more familiar in the coming years: credit default swaps, subprime mortgage lending, tranches, CDOs. The gore and detail of the cover that had been constructed around scams and fraud at the broadest level was audible in the voices of interviewers and guests. There was a tinge of disbelief within their attempts to explain what these terms meant and how they had gotten us all (!) into so much peril. It was as close to 1929 as we had come and potentially far worse – so extensively had the giant vampire squid of financial engineering welded its tentacles to every sector. Housing, banking, investing, construction, debt, bonds… this is business America now, and every other activity is vulnerable to its caprice. It was the stretch run of a presidential election as well; one candidate tried to suspend the campaign, the other fortunately tried to hold things together.

In early September 2008, I drove down to Charleston to visit a cousin who had recently suffered a terrible accident. Throughout the drive I listened to extended public radio reports on an evolving calamity: the collapse of Lehman Brothers financial services firm. The horror that the government was going to allow such a large firm to go under was decorated with the baroque gadgetry of terms that would become more familiar in the coming years: credit default swaps, subprime mortgage lending, tranches, CDOs. The gore and detail of the cover that had been constructed around scams and fraud at the broadest level was audible in the voices of interviewers and guests. There was a tinge of disbelief within their attempts to explain what these terms meant and how they had gotten us all (!) into so much peril. It was as close to 1929 as we had come and potentially far worse – so extensively had the giant vampire squid of financial engineering welded its tentacles to every sector. Housing, banking, investing, construction, debt, bonds… this is business America now, and every other activity is vulnerable to its caprice. It was the stretch run of a presidential election as well; one candidate tried to suspend the campaign, the other fortunately tried to hold things together. The stupidity of millions, millions of individually stupid decisions, has brought a spiteful revolution to its denouement. Or a screaming kid to its mall, whichever you prefer.

The stupidity of millions, millions of individually stupid decisions, has brought a spiteful revolution to its denouement. Or a screaming kid to its mall, whichever you prefer. In tribute to the great

In tribute to the great  Peter Singer’s 1975 book

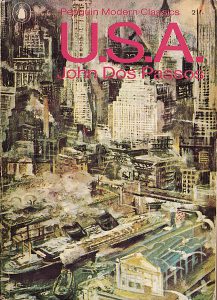

Peter Singer’s 1975 book  Published in 1938 as USA, the trilogy recounts the evolution of American society during the first three decades of the 20th century. The jazz age had been engulfed by the stock market crash, the depression, and the rise of fascism. Dos Passos was still a communist, mindful of the gaps between rich and poor in America. The first volume,

Published in 1938 as USA, the trilogy recounts the evolution of American society during the first three decades of the 20th century. The jazz age had been engulfed by the stock market crash, the depression, and the rise of fascism. Dos Passos was still a communist, mindful of the gaps between rich and poor in America. The first volume,  “That’s right, Robin.”

“That’s right, Robin.”