Consider the names we’ve had for it already: the greenhouse effect. Global warming, and it’s corollary, AGW. Climate change. Treating a planet warming from CO2 like a parlor game, and especially by using the tobacco industry, to see how long we can maintain our ignorance up to and even about whether anything can be done about it takes special effort. And Exxon has had their best people on it since the 70’s:

There’s a sense, of course, in which one already assumed that this was the case. Everyone who’s been paying attention has known about climate change for decades now. But it turns out Exxon didn’t just “know” about climate change: it conducted some of the original research. In the nineteen-seventies and eighties, the company employed top scientists who worked side by side with university researchers and the Department of Energy, even outfitting one of the company’s tankers with special sensors and sending it on a cruise to gather CO2 readings over the ocean. By 1977, an Exxon senior scientist named James Black was, according to his own notes, able to tell the company’s management committee that there was “general scientific agreement” that what was then called the greenhouse effect was most likely caused by man-made CO2; a year later, speaking to an even wider audience inside the company, he said that research indicated that if we doubled the amount of carbon dioxide in the planet’s atmosphere, we would increase temperatures two to three degrees Celsius. That’s just about where the scientific consensus lies to this day. “Present thinking,” Black wrote in summary, “holds that man has a time window of five to ten years before the need for hard decisions regarding changes in energy strategies might become critical.”

Those numbers were about right, too. It was precisely ten years later—after a decade in which Exxon scientists continued to do systematic climate research that showed, as one internal report put it, that stopping “global warming would require major reductions in fossil fuel combustion”—that NASA scientist James Hansen took climate change to the broader public, telling a congressional hearing, in June of 1988, that the planet was already warming. And how did Exxon respond? By saying that its own independent research supported Hansen’s findings? By changing the company’s focus to renewable technology?

That didn’t happen. Exxon responded, instead, by helping to set up or fund extreme climate-denial campaigns.

It’s not enough to know this, nor to merely compare it to the efforts of Big Tobacco. It will require a systematic dismantling of Big Oil because as presently organized, only it will decide when or if anything is to be done. Listen to the presidential candidates on the right. Big Oil’s work has been done and done well. The best tactic – accuse your opponents of what you yourself have been doing – remains operable. The charge that scientists support climate science because it brings in big grant money is not only laughable in terms of the profits realized by research scientists in the energy companies employ, not to mention by candidates for higher office.

As much as they blame other forces, it is rapacious capitalists that threaten capitalism, though the misery is amplified by the fact that so many canaries will have to be tried and executed before we understand how dangerous the mine is.

Via Erik at LGM.

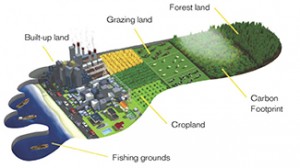

Extensive studies done after Katrina verified what lifelong residents of southeastern Louisiana already knew: Unless the rapidly disappearing wetlands are made healthy again, restoring the natural defense, New Orleans will soon lay naked against the sea (see satellite image, below).

Extensive studies done after Katrina verified what lifelong residents of southeastern Louisiana already knew: Unless the rapidly disappearing wetlands are made healthy again, restoring the natural defense, New Orleans will soon lay naked against the sea (see satellite image, below).

Our best hope for carbon reduction is steep price drops in the cost of generating electricity by wind and solar; in the cost of installing wind turbines and solar panels; and in the cost of storing energy in batteries. If those price drops are achieved, we’ll head toward vast reductions in emissions regardless of what the EPA does. No one is going to pay 12 cents a kilowatt hour for electricity (our current national average) if it can be had for 2 cents a kilowatt hour, all other things being equal.

Our best hope for carbon reduction is steep price drops in the cost of generating electricity by wind and solar; in the cost of installing wind turbines and solar panels; and in the cost of storing energy in batteries. If those price drops are achieved, we’ll head toward vast reductions in emissions regardless of what the EPA does. No one is going to pay 12 cents a kilowatt hour for electricity (our current national average) if it can be had for 2 cents a kilowatt hour, all other things being equal.