This very poignantly familiar article on How to get Americans to care about a War includes most all the essentials that pour drama, apathy, and avoidance into a toxic stew of catastrophe and suffering around the world.

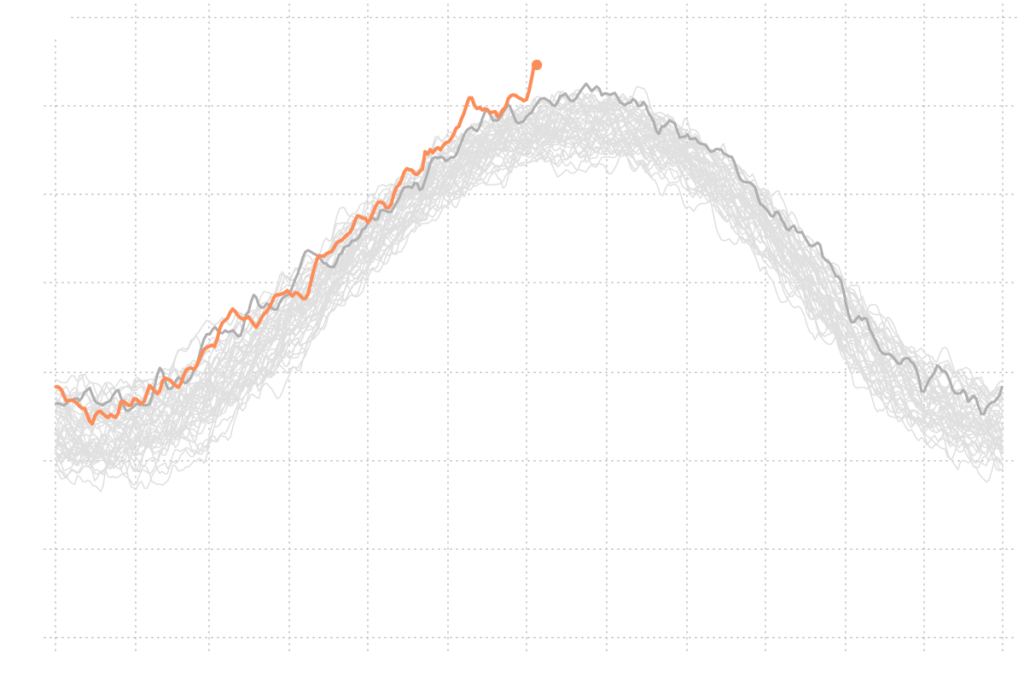

The dangers issuing from obtuse and deliberate lack of awareness resonate with a study published in the journal Nature this week. The research frames the economic damage that will come from climate change, a projections-based picture of missed opportunities of the world we might have been living in 2050, had different choices been made – in voting booths and boardrooms, primarily.

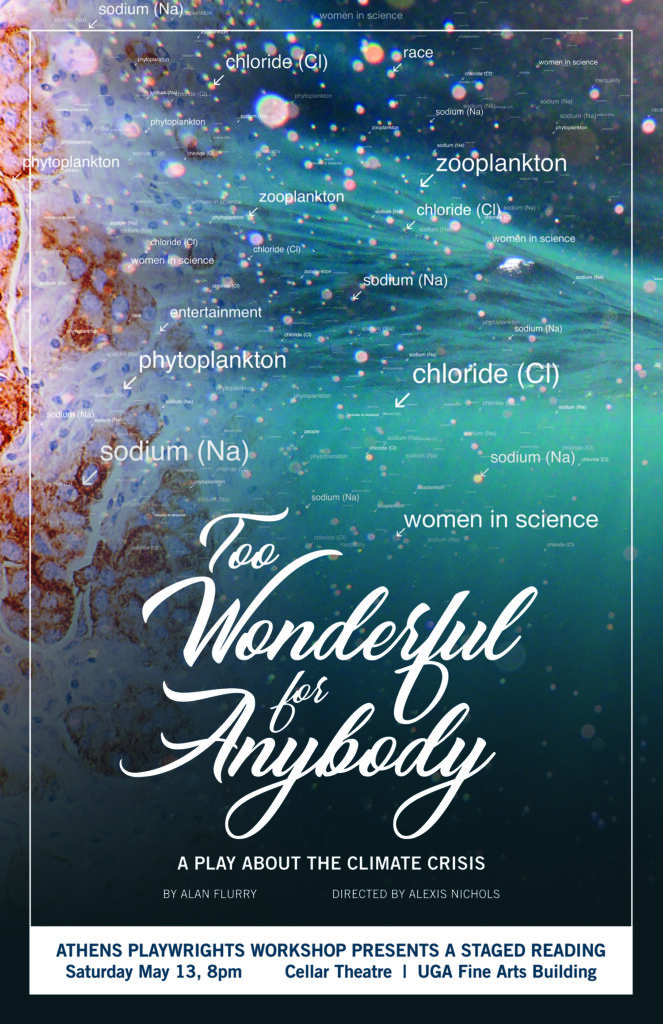

We can play the blame game of ‘who started what,’ and maybe we should to [better] inform future results. But that fact certain people around the world of whom Americans are definitely some can continue to play games and distract ourselves from wars and global warming is all of a part. The distraction game itself is seen as a growth industry in many quarters, and so of course it is. In the face of getting serious about consumer choices and investment portfolios as incentives or tradeoffs to be considered in the calculations to do anything about massive abstractions like ocean temperatures [not abstract at all, -ed] future choices and prosperity are frittered away.

Getting people to care about things that matter as just another version of vying for your attention is a triumph of marketing and failure of education. It is no indictment of childhood to tell people to grow up. It’s even in the one book they use to ban other books.

Also: put the damn books back. It’s embarrassing. What are we, chil–?