It’s no stretch to suggest that quantifying life as we know it not in terms of quality but economic growth leaves everyone a bit empty, a bit lesser for the experience, such as it is.

Numbers are fine, can be fun, even. Inspiring. Take Clairaut’s Theorem, as just one example. Among the heights of the Enlightenment – there were several – the eighteenth-century French mathematicians/philosophers Alexis Clairaut and Pierre Louis Maupertuis led an expedition to Lapland in the Arctic Circle (in the 1730’s) in order to measure a single degree of the median arc. The goal was to calculate the shape of the Earth, and validate whether Newton was correct in his Principia where he theorized it was an ellipsoid shape.

In disagreeing with Newton’s theory, Clairaut suggested not only that the Earth is of an oblate ellipsoid shape, but it is flattened more at the poles and is wider at the center. You can imagine the controversial this unleashed among scholars of the day, and Clairaut leaned in, full tilt. He courted the fight and published work in the 1740’s that promoted Clairaut’s Theorem, which connects the gravity at points on the surface of a rotating ellipsoid with the compression and the centrifugal force at the equator.

Under the assumption that the Earth was composed of concentric ellipsoidal shells of uniform density, Clairaut’s theorem could be applied to it, and allowed the ellipticity of the Earth to be calculated from surface measurements of gravity. This proved Sir Isaac Newton’s theory that the shape of the Earth was an oblate ellipsoid. In 1849 George Stokes showed that Clairaut’s result was true whatever the interior constitution or density of the Earth, provided the surface was a spheroid of equilibrium of small ellipticity. [wikipedia]

Provides interesting context to our jokey notion about “views differ on the shape of the Earth.” There’s an amazing book about all of this and more that centers on Madame Du Châtelet, erstwhile mistress of Voltaire who translated Newton’s Principia.

Fascination may be in the eye of the beholder. However, a focus on economic growth beyond the point where it may be healthy, productive, even possible, disassociates us from even the power of numbers themselves. Growth becomes its own ends and we, captive to the destruction its portends, stand idly by and make nervous jokes about issues long settled, amidst our intellectual withering and spiritual decay.

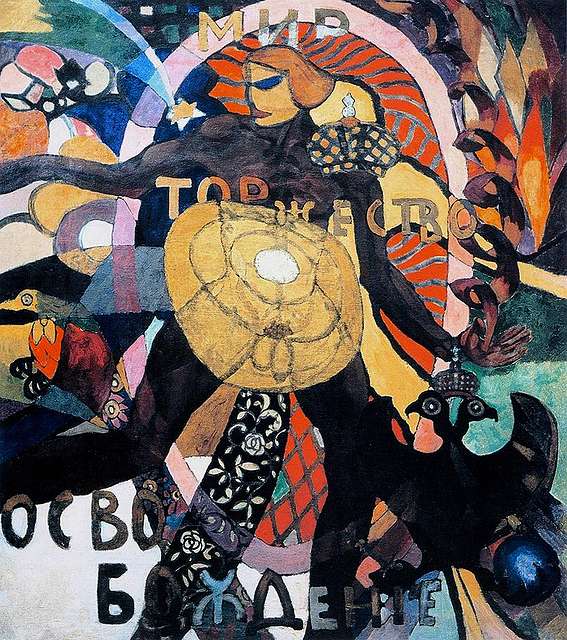

Image: [shiny)Detail of a painting by Lou Kregel.