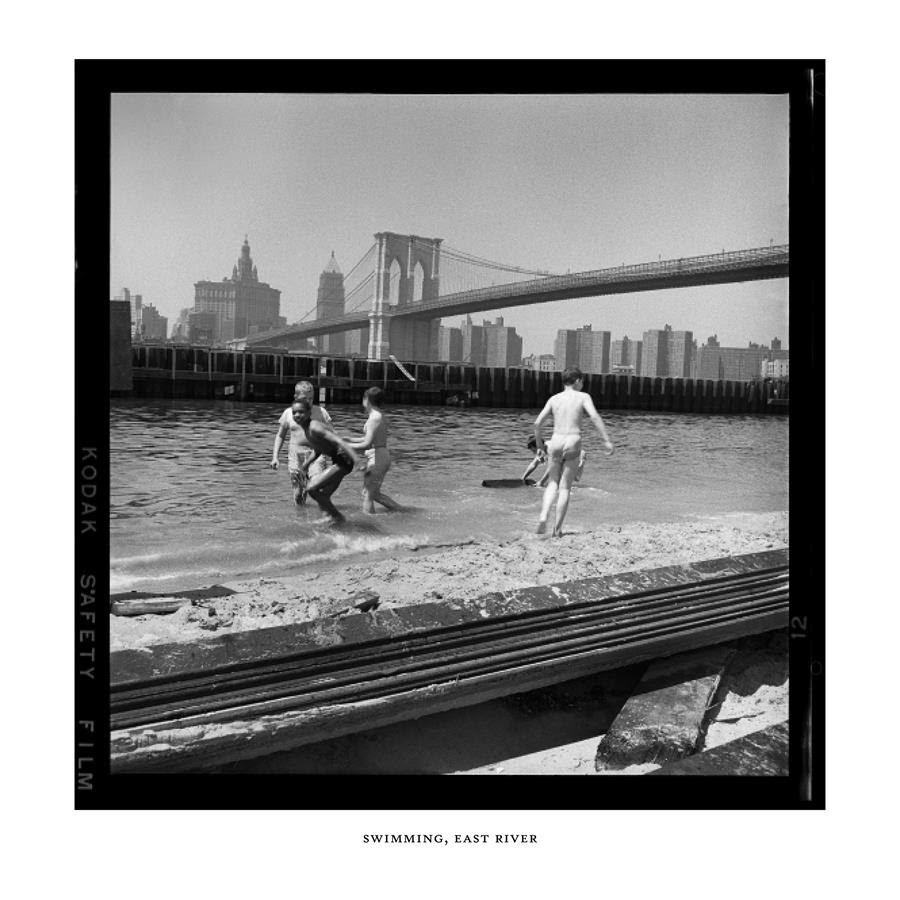

With the Lost Photographs of David Attie

by Truman Capote

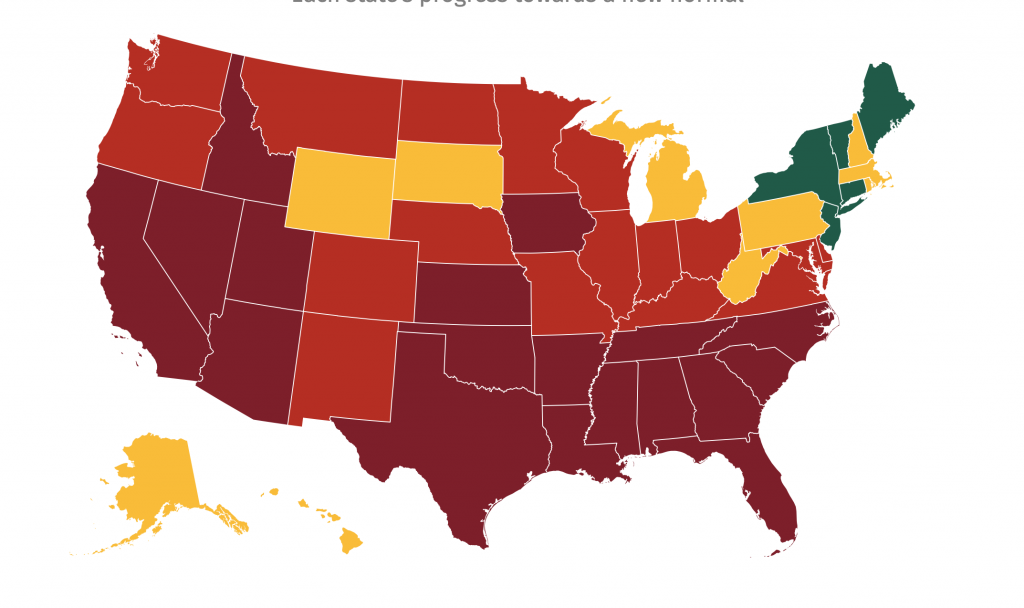

“To the Finland Station” is different. The structure is simple: the decline of the bourgeois revolutionary tradition after the French Revolution, as Wilson sees it reflected in the writings of Jules Michelet, Ernest Renan, Hippolyte Taine, and Anatole France; the emergence of revolutionary socialism, seen through the writings of Saint-Simon, the communitarians Charles Fourier and Robert Owen, and Marx and Engels; the triumph of Communism, illustrated by the careers of Lenin and Trotsky. There are things Wilson minimized that would have complicated this narrative: the persistence of a non-Communist socialist ideal in Western Europe; the liberal tradition in Russian politics (to which Nabokov’s father belonged); the success and failure of the Mensheviks, of whom Wilson did not make much. And, of course, if the book were being written now, the vicious side of Marxist and Leninist thought, mostly a subtext in Wilson’s account, would guide the narrative, and the story would touch down in Siberia or Berlin rather than at the Finland Station.

But we don’t read “To the Finland Station” as a book about the Russian Revolution anymore. What draws us now is the subtitle: “A Study in the Writing and Acting of History.” History is the true subject of Wilson’s book, and what he evokes is what it felt like to believe—as Vico and Michelet, Fourier and Saint-Simon, Hegel and Marx, Lenin and Trotsky all believed—that history holds the key to the meaning of life. The evocation is successful because when Wilson began writing “To the Finland Station” he believed in history, too. He thought that history had a design, and that the Depression was an event fully comprehensible within the context of that design: it was the long-predicted collapse of the capitalist order. “To the Finland Station” is valuable as a window on the nineteenth century, but it is also a poignant artifact of the nineteen-thirties, a time when many people thought that history was something you could get on the right side or the wrong side of. It was an idea indistinguishable from faith, and Marx was one of its prophets.

It’s a dirty foul that American school kids don’t learn about Jules Michelet. We must get beyond this aversion to learning about certain histories, be it socialism or the 1619 project, whatever. The less you know, well, the less you know and suddenly another Trump falls off the turnip truck yesterday and the corporate types get summoned to the cut of his jib, obscuring the more accurate assessments, ‘something just ain’t right with that boy.’

Image by David Attie, 1959, from the NYRB