High-tech city-region conceptual nightmares get all the attention:

Gray had signed on to a city-building exercise so ambitious that it verges on the fantastical. An internal Neom “style catalog” viewed by Bloomberg Businessweek includes elevators that somehow fly through the sky, an urban spaceport, and buildings shaped like a double helix, a falcon’s outstretched wings, and a flower in bloom. The chosen site in Saudi Arabia’s far northwest, stretching from the sun-scorched Red Sea coast into craggy mountain badlands, has summer temperatures over 100F and almost no fresh water. Yet, according to MBS and his advisers, it will soon be home to millions of people who’ll live in harmony with the environment, relying on desalination plants and a fully renewable electric grid. They’ll benefit from cutting-edge infrastructure and a regulatory system designed expressly to foster new ideas—as long as those ideas don’t include challenging the authority of MBS. There may even be booze. Neom appears to be one of the crown prince’s highest priorities, and the Saudi state is devoting immense resources to making it a reality.

Yet five years into its development, bringing Neom out of the realm of science fiction is proving a formidable challenge, even for a near-absolute ruler with access to a $620 billion sovereign wealth fund. According to more than 25 current and former employees interviewed for this story, as well as 2,700 pages of internal documents, the project has been plagued by setbacks, many stemming from the difficulty of implementing MBS’s grandiose, ever-changing ideas—and of telling a prince who’s overseen the imprisonment of many of his own family members that his desires can’t be met.

The consultants love it, we can be sure. But it’s not just this or similar grandiose, wrecked visions. Every municipality – and they are multitude – that prioritizes roads and personal automobiles faces an acute reckoning. The sci-fi setting isn’t even necessary, the merely ubiquitous [ed. pedestrian? deja ] cities and towns that strand people just far enough away from school, food, work, and/or play represent an invisible disaster, one we don’t understand, one we will seek to blame on anyone but ourselves and in so doing, soften the ground for fascist inroads. It’s pretty straightforward and has everything to do with removing the humanity from daily interactions.

Examples like Neom could do a better job of serving to remind us of the chief failings of our own unworkable burgs, keep us off the hinterlands and more engaged in town life.

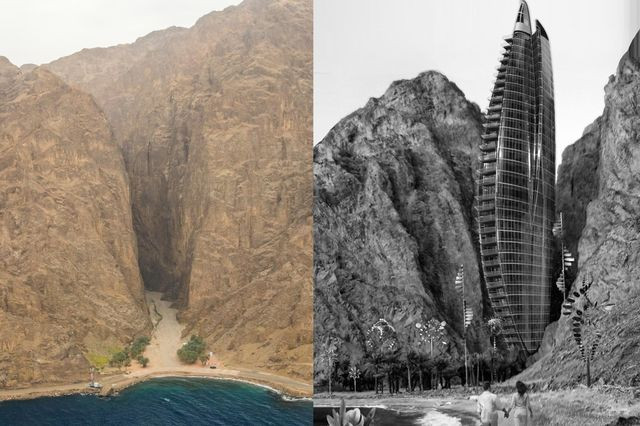

Image: A planned seaside hotel. Photographer: Iman Al-Dabbagh

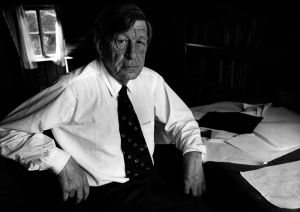

No need to resist this. From an interview with W.H. Auden, published in

No need to resist this. From an interview with W.H. Auden, published in