Getting back to our actual life, I’ll be reading “Concluding” now and finding out more about this now-obscure mid-century wonder:

Getting back to our actual life, I’ll be reading “Concluding” now and finding out more about this now-obscure mid-century wonder:

At the time, Green was in his late forties and the author of nine novels, including “Living,” “Party Going,” and “Loving,” and a memoir, “Pack My Bag.” His stock was high among fellow-writers. In a 1952 Life profile, W. H. Auden was quoted calling him “the best English novelist alive.” The following year, T. S. Eliot, talking to the Times, cited Green’s novels as proof that the “creative advance in our age is in prose fiction.” But Green had never been a popular success. In 1930, Evelyn Waugh had reviewed “Living,” Green’s novel about Birmingham factory life, under the headline “A Neglected Masterpiece.” It was the first of several dozen articles that bemoaned Green’s lack of acceptance and helped bind his name as closely to the epithet “neglected” as Pallas Athena is to “bright-eyed.”

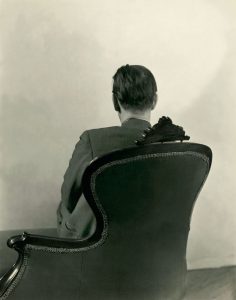

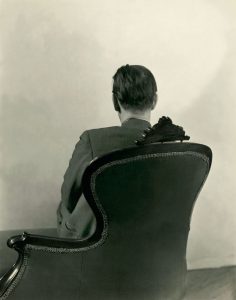

Waugh blamed philistine book reviewers, but he knew that Green’s image hadn’t helped. “From motives inscrutable to his friends, the author of Living chooses to publish his work under a pseudonym of peculiar drabness,” he wrote. Green was born Henry Vincent Yorke, to a prominent Gloucestershire family, and he worked as the managing director of H Pontifex & Sons Ltd., a manufacturing company purchased by his grandfather; he presented himself as a Sunday writer. (Where other novelists might serve as secretary of pen, Green did a stint as chairman of the British Chemical Plant Manufacturers’ Association.) He claimed that he wrote under an assumed name in order to hide his writing from colleagues and associates. The Life profile, “The Double Life of Henry Green,” had the subtitle “The ‘secret’ vice of a top British industrialist is writing some of Britain’s best novels.” But Green’s first book, “Blindness,” was published in 1926, while he was at Oxford, and a desire for privacy characterized much of his behavior. After a certain point, he refused to have his portrait taken. Dundy had first recognized him from a Cecil Beaton photograph that showed only the back of his head.

As a fan of Auden, I take the above characterization with great seriousness. The undermining of omniscience on the part of the narrator is also serious business, to which I will attend.

PHOTOGRAPH BY CECIL BEATON / CONDÉ NAST