My dear Theo,

I read an announcement in L’Intransigeant that there’s going to be an exhibition of the Impressionists at Durand-Ruel — there’ll be some works by Caillebotte —I’ve never seen anything of his, and wanted to ask you to write and tell me what they’re like — there are certainly other noteworthy things too.

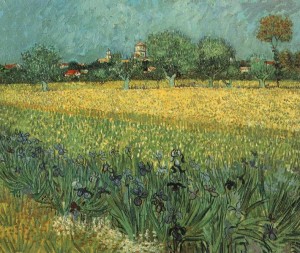

I sent you some more drawings today, and I’m adding two more. They’re views taken from a rocky hill from which you can see in the direction of the Crau (an area from which a very good wine comes), the town of Arles and in the direction of Fontvieille. The contrast between the wild and romantic foreground — and the broad, tranquil distant prospects with their horizontal lines, shading off until they reach the chain of the Alpilles — so famous for the great feats of climbing of Tartarin, P.C.A., and the Alpine Club. This contrast is very picturesque.

The two drawings that I’m now adding afterwards will give you an idea of the ruin that crowns the rocks. But is it worth the trouble of making frames for this Dordrecht exhibition? I find it so silly and I’d prefer not to be part of it.

I prefer to believe that Bernard or Gauguin will exchange drawings with us in which the Dutch will see nothing.

Have you met the Dane Mourier-Petersen — he’ll have brought you another two drawings as well.

He studied to be a doctor, but I suppose he was discouraged in that by the student life, discouraged by both his pals and his professors. He never said anything to me about it, though, except that he once declared: ‘but doctors kill people’.

When he came here he was suffering from a nervous condition that came from the strain of the examinations. How long has he been doing painting — I don’t know — he’s certainly made little progress as a painter, but he’s good as a pal and he looks at people and often judges them very accurately. Could there be a possible arrangement whereby he could come to live with you? As far as intelligence goes, I think he’d be far more preferable to that Lacoste, of whom I don’t think highly, I don’t know why. You’ve absolutely no need of 6th-rate Dutchmen or worse, who when going back to their country do nothing but say and do idiotic things. A dealer in paintings is, unfortunately, more or less a public figure.

Anyway, there’s no serious harm done.

The Swede is from a good family, he has order and regularity in his means of support, and as a man he makes me think of those characters Pierre Loti creates11. For all that he’s phlegmatic, he has a good heart.

I plan to do a lot more drawing. It’s already jolly hot, I can assure you.

I must add an order for colours to this letter — however, if you’d prefer not to get them immediately I’d do a few more drawings and wouldn’t lose anything by it.

I’ll also divide the order into two according to what would be more urgent or less.

What’s always urgent is to draw, and whether it’s done directly with a brush, or with something else, such as a pen, you never do enough.

I’m trying now to exaggerate the essence of things, and to deliberately leave vague what’s commonplace.

I’m delighted that you’ve bought the book on Daumier — but if you could add to that by buying some more of his lithographs that would be absolutely good — because in the future Daumiers won’t be easy to get hold of.

How’s your health, have you seen père Gruby again? I’m inclined to believe he exaggerates your heart condition a bit, to the detriment of the need to treat you rigorously for your nervous system. Well, he’ll certainly realize it as you follow his treatment; with Gruby you’ll last, but unfortunately for us père Gruby himself won’t last, because he’s getting old and when we need him the most he won’t be there any more.

I’m thinking more and more that we shouldn’t judge the Good Lord by this world, because it’s one of his studies that turned out badly. But what of it, in failed studies — when you’re really fond of the artist — you don’t find much to criticize — you keep quiet. But we’re within our rights to ask for something better. We’d have to see other works by the same hand though. This world was clearly cobbled together in haste, in one of those bad moments when its author no longer knew what he was doing, and didn’t have his wits about him. What legend tells us about the Good Lord is that he went to enormous trouble over this study of his for a world. I’m inclined to believe that the legend tells the truth, but then the study is worked to death in several ways. It’s only the great masters who make such mistakes; that’s perhaps the best consolation, as we’re then within our rights to hope to see revenge taken by the same creative hand. And — then — this life — criticized so much and for such good, even excellent reasons — we — shouldn’t take it for anything other than it is, and we’ll be left with the hope of seeing better than that in another life. Handshake to you and to Koning.

Ever yours,

Vincent

I hope to have news from you tomorrow, otherwise I’d be in quite a tight corner as I only have money left for tomorrow, Sunday.

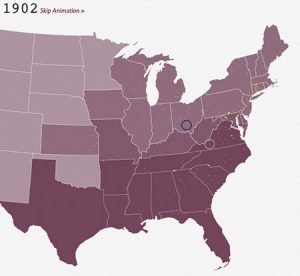

When it all began is as clear of a question as when it might end. Actual Nazis on violent parade (is there another kind of Nazi parade?) in a public square has brought the question of white supremacy out of the shadows for the time being. Hopefully the moment lasts a while longer to

When it all began is as clear of a question as when it might end. Actual Nazis on violent parade (is there another kind of Nazi parade?) in a public square has brought the question of white supremacy out of the shadows for the time being. Hopefully the moment lasts a while longer to