Is it possible? Thanks to Flagpole for the coverage of the readings for my new project:

Suppose you, unlike most people, start taking climate change seriously. Suppose, too, that your skills lie in areas having to do with communication—you’re a writer, a publicist, a blogger; you interview people on television. So when you start taking something seriously, something as all-encompassing as climate change, you naturally begin thinking about how to share your climate concerns, which, you realize, should concern us all, but which you know are far from most people’s consciousness.

Climate change is so far from our everyday lives (and so near) that it is almost impossible for the finest scientific and academic minds to wake us up. But if you’re Alan Flurry, who has all the communication skills mentioned above, plus more (he’s a drummer), you’re still going to have a go at finding a vehicle that tries to bridge the wide gap between everyday and everywhere.

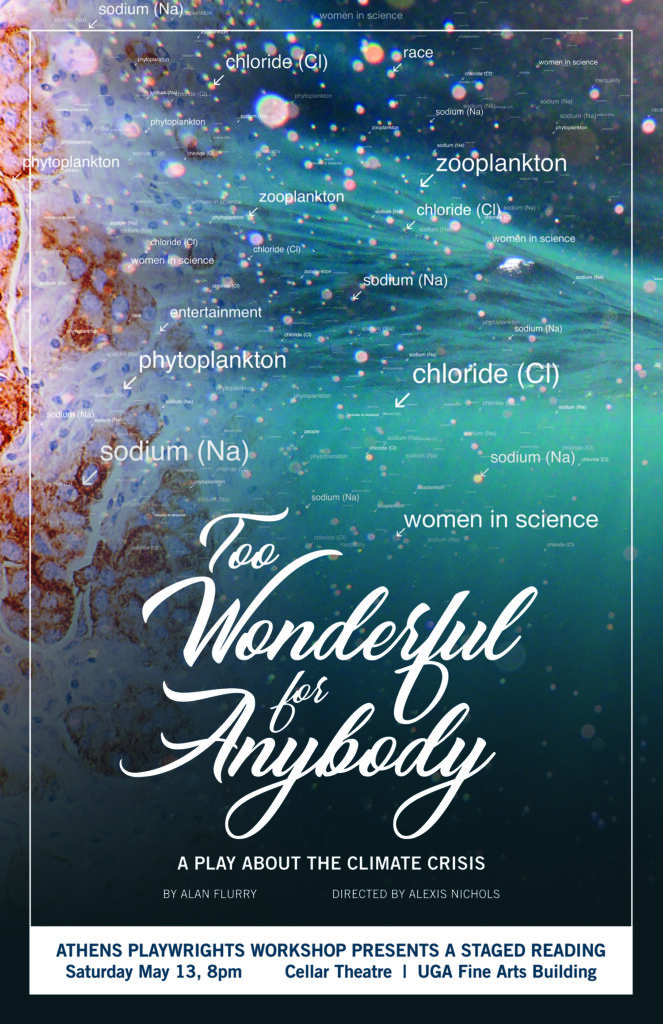

Alan’s solution is to write a play. You say that’s more likely to put them to sleep than wake them up. Nevertheless, a communicator communicates, and Alan has written a play about climate change, which will have a staged reading a couple of times next week, directed by Alexis Nichols.

Flurry uses the device of a play within a play, or actually several plays within a play. The main through-line belongs to the character known as “Director.” Director, you see, is staging a play and is at the point of read-throughs when he begins musing with Adam, one of the actors. In fact, Director, thanks to split staging and multiple time frames, is staging several plays, but the one foremost in his mind is about climate change. So, we’ve got all the plays in the process of production, but Director continues to bring us back to the main event—his preoccupation with climate change.

Hopefully coming to stage near you in the near future.