Even when

Born in Paris in 1911, Bourgeois suffered more than the usual number of grievous blows to the psyche, and her inner life stayed tightly wrapped around their memory. War, illness, sexual jealousy, mental instability were all things she witnessed in her first decade, and she never forgot—or forgave—any of them. As a teenager she learned that the attractive young Englishwoman who lived with the family as a tutor was also her father’s mistress, and this betrayal in particular was something she never got over. In addition, or perhaps in response, her mother was fragile and often ill, and young Louise became her companion at various spas and treatment centers; she was released from her caretaker role by her mother’s death when she was twenty-one.

After the loss of her mother, and encouraged by her charming and tyrannical father, Bourgeois started a small business selling works on paper, prints, and illustrated books out of a corner of the family’s tapestry workshop on the Boulevard Saint-Germain. To acquire her stock, she scoured the auction houses and book dealers, and she seems to have absorbed, almost overnight, the dominant graphic styles of the day. She had a particular affinity for Bonnard and Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as other artists who used the illustrated book form, which was then in vogue. Something about these livres d’artiste, as they were known—the way they combined text and pictures, and the way the image was printed from engraving or etching plates, the whole satisfying feel in the hand of beautifully made paper embossed with rectangles of finely drawn tones of gray—formed the template for how Bourgeois would think about her own art, on and off, for the rest of her life.

Have a template for how you think what matters most to you. Seems like all the advice anyone might need.

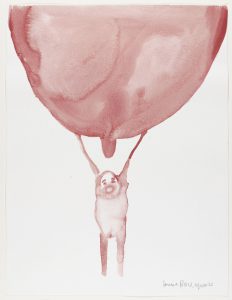

Image: Louise Borgeois: Self Portrait, 2007. MOMA

Since everything seems to be

Since everything seems to be

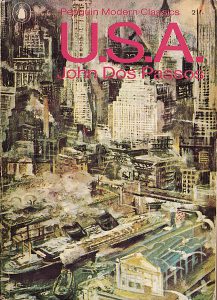

Published in 1938 as USA, the trilogy recounts the evolution of American society during the first three decades of the 20th century. The jazz age had been engulfed by the stock market crash, the depression, and the rise of fascism. Dos Passos was still a communist, mindful of the gaps between rich and poor in America. The first volume,

Published in 1938 as USA, the trilogy recounts the evolution of American society during the first three decades of the 20th century. The jazz age had been engulfed by the stock market crash, the depression, and the rise of fascism. Dos Passos was still a communist, mindful of the gaps between rich and poor in America. The first volume,  No need to resist this. From an interview with W.H. Auden, published in

No need to resist this. From an interview with W.H. Auden, published in