At the outset of the newest year, with walls incoherently at the center of our discourse as we contemplate how best to keep people out rather how best to help them up, a bit of perspective provides a reminder that we might be mixed up about parts of the story:

For most of their history, humans lived in tiny egalitarian bands of hunter-gatherers. Then came farming, which brought with it private property, and then the rise of cities which meant the emergence of civilization properly speaking. Civilization meant many bad things (wars, taxes, bureaucracy, patriarchy, slavery…) but also made possible written literature, science, philosophy, and most other great human achievements.

Almost everyone knows this story in its broadest outlines. Since at least the days of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, it has framed what we think the overall shape and direction of human history to be. This is important because the narrative also defines our sense of political possibility. Most see civilization, hence inequality, as a tragic necessity. Some dream of returning to a past utopia, of finding an industrial equivalent to ‘primitive communism’, or even, in extreme cases, of destroying everything, and going back to being foragers again. But no one challenges the basic structure of the story.

There is a fundamental problem with this narrative.

It isn’t true.

Overwhelming evidence from archaeology, anthropology, and kindred disciplines is beginning to give us a fairly clear idea of what the last 40,000 years of human history really looked like, and in almost no way does it resemble the conventional narrative. Our species did not, in fact, spend most of its history in tiny bands; agriculture did not mark an irreversible threshold in social evolution; the first cities were often robustly egalitarian. Still, even as researchers have gradually come to a consensus on such questions, they remain strangely reluctant to announce their findings to the public – or even scholars in other disciplines – let alone reflect on the larger political implications. As a result, those writers who are reflecting on the ‘big questions’ of human history – Jared Diamond, Francis Fukuyama, Ian Morris, and others – still take Rousseau’s question (‘what is the origin of social inequality?’) as their starting point, and assume the larger story will begin with some kind of fall from primordial innocence.

It’s from earlier this year in 2018, but read the whole, etc. There is no ‘them’ but there are assumptions and many of ours may be wrong or at least worth re-considering.

Banksy image from the original.

Via LGM, the approaching

Via LGM, the approaching  Noted early twentieth century cultural signifier Eau de Nil wends it way from Flaubert in Egypt to Hitchcock to a fresh moment in the sun thanks to a

Noted early twentieth century cultural signifier Eau de Nil wends it way from Flaubert in Egypt to Hitchcock to a fresh moment in the sun thanks to a

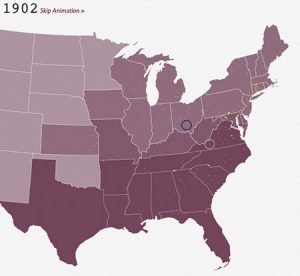

When it all began is as clear of a question as when it might end. Actual Nazis on violent parade (is there another kind of Nazi parade?) in a public square has brought the question of white supremacy out of the shadows for the time being. Hopefully the moment lasts a while longer to

When it all began is as clear of a question as when it might end. Actual Nazis on violent parade (is there another kind of Nazi parade?) in a public square has brought the question of white supremacy out of the shadows for the time being. Hopefully the moment lasts a while longer to  It’s back to school time! Lunch pails and school slates may have given way to Uber eats and iPads, but one anachronism that remains is the ability for donors to get their kids into the best schools. With the Trump Justice Department launching a dubious new project targeting discrimination against white students in university admissions policies, I’m not going to explain why a diverse population in any university is not just a nice thing, but inarguably a crucial component in a

It’s back to school time! Lunch pails and school slates may have given way to Uber eats and iPads, but one anachronism that remains is the ability for donors to get their kids into the best schools. With the Trump Justice Department launching a dubious new project targeting discrimination against white students in university admissions policies, I’m not going to explain why a diverse population in any university is not just a nice thing, but inarguably a crucial component in a