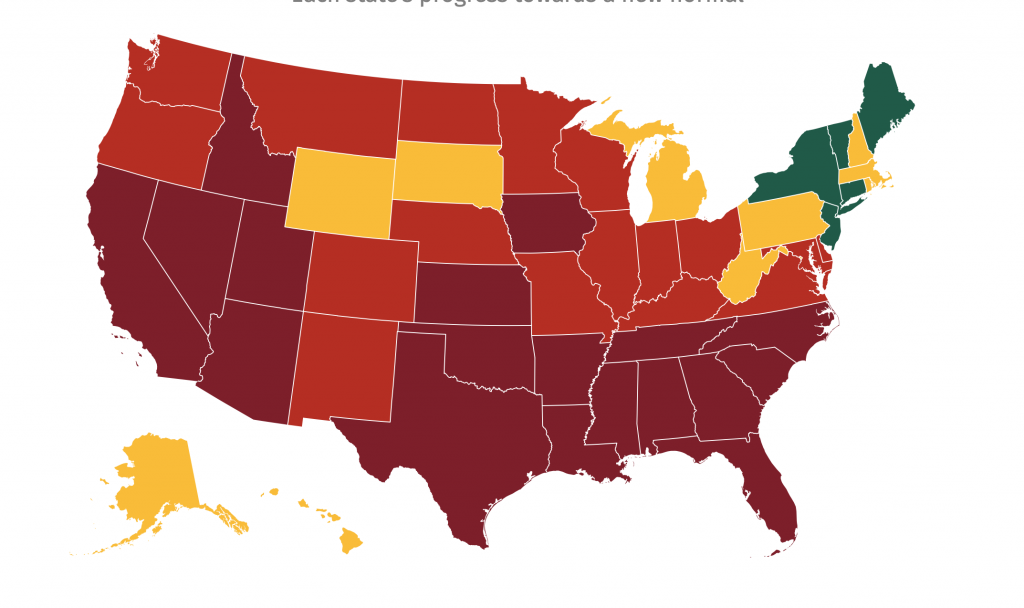

More ridiculous by the day, wasted time, wasted lockdown, wasted lives for reasons unexplained. People are not human resources.

Stuffed in a new thing:

He didn’t mean to use the word enemy, but now that he had, it was difficult to take back. What’s worse is that he was less confused than ever. Sides had been taken and _____ knew, like people always know, what side they are actually on. The more dangerous slide waited at the very beginning of every turn, steeper for those shod with the wrong footing or none at all, quick decisions about direction that appeared at first correctable were only so because of the misplaced training. Maybe the training had all been designed, at the turn away from classical disciplines, to produce this very result, but choosing that cynicism inferred a luxury it had also already eliminated. The speed and efficiency were proportional to the devastation. People completely bought into how fast everything was happening even though nothing outside of them had changed. Nothing beyond their own habits and consumptions against missing out, losing something nonexistent, closing an opportunity – ideas that had long been propagated on the under-educated.

Requiescat in pace, John Lewis. The great man.