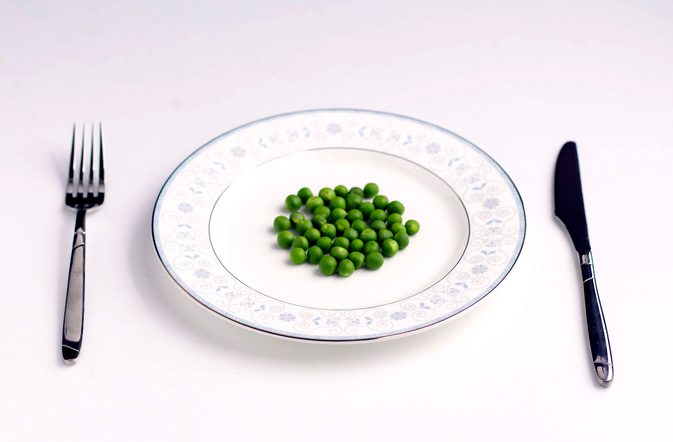

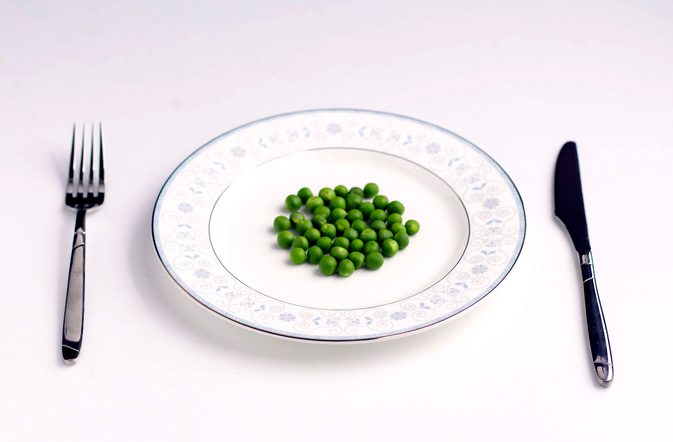

Caught but not certain. Laid low and silenced by the voices within, he withdrew from the room seriously, like he had a better reason than even a phone call to take. As though he would be relieved to be relieved of his colleague’s wife and his colleague for a moment, even of his own wife. She looked at her guests to see their reaction follow the silence created by the ringing but there came no obvious offense to the one face they seemed to share, looking in across the table. Green peas, everyone had green peas still on their plates, that’s what she noticed more. Maybe they had been no good, no good at all, and perhaps she wished that had been the reason her husband had left the room with a weak excuse. Perhaps.

All she knew now was that their conversation which had been so lively moments before had ceased, as if awaiting his return before it could more properly resume. This unnerved her. Was she so incapable of conversing that her guests needed him? Needed him more? Had she not attended _______ with him, earned better grades and knew more people, giver her own thoughts about a master’s in archeology a childish look back after it was decided, somehow fucking decided, that he would attend medical school as if in her stead, and indeed in the stead of many things? She had admired his boyish streak then, encouraged him and had witnessed how, in subscribing to some manly beliefs that would provide dark difficulties for the boy, he was seeding the luxury of a future utility. And thus was performed a type of acrobatics that made sense, even with gravity, even in medical school with her remembering school in all the same fall when they had been anything but slaves to the future and even their own commitment had more to do with love than anything beyond it. Another fall had rolled around, and she had grown painfully accustomed to waiting on him, now over cold peas and two frosty guests that she’d considered liking during the cold banana appetizer.

She could hear him talking in the next room and wondered why he had chosen a phone so close to where the guests waited, perhaps to let them overhear the muffled sound of his voice and further convey the seriousness his attention warranted. But she knew there was more, as he had stopped subscribing so closely to concerns of what others thought of him months before; it was reminiscent of giving up exercising for an injury. He nursed his injury, and let his wife answer the door, bake the ham and light the candles. He just breezed in looking fresh and nibbled, made excuses to leave whenever his hard-fought trappings became too much of themselves. Themselves in a painless light of caricature by which his accomplishments more resembled responsibilities. She hoped he might come back and say he had to leave, the phone call, ‘you know, they need me,’ he would say. She would then feel no further obligation in humoring the seriousness of her guests, no requirement to answer their questions about the old house or the painting in the hall like some multiple choice questions on a master’s exam she never took. She had her own calls to make.

But he didn’t. He returned and claimed his seat next to the wife of his colleague before his cold peas and across from his own sexy wife he hadn’t seen in years. He made a small joke about the presence of seamen at which his wife laughed out loud at exactly the wrong time so that she laughed alone and the other three just stared at her, and he could not even finish his joke then because all of a sudden, he was unsure what was so funny. He knew something was eating him alive, he even saw the teeth marks, but without the courage to stop it, so he could only blame her and claim as his evidence those times when she laughed out of place and embarrassed him. The colleague and his wife sat as one, unsure in movement and embarrassed themselves. But not as part of the fray; they refused to see what they could easily identify as a war on the cold pea horizon and were intent on remaining frozen, afraid even to look at the opposing forces. Silver clanged to china because now everyone, except the wife – who saw many things – everyone saw only one thing as the last recourse and the only thing to do until there was another opening like a beautiful phone call to be taken: eat the peas.

“Would anyone like more wine?” she watched him say with genuine curiosity in his voice. He rose at his place at the table as the colleague and his wife agreed certainly and without doubt that yes, they would love some more wine. “What about you, honey?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I think I want Scotch. Does anybody want Scotch?” she asked with a different curiosity. The husband began to sink where he stood, almost reaching his chair again. He had been stabbed by her once again, he thought. The guests watched them and looked at her with the assurance that they definitely did not care for, could not more fervently beg against – it was only Tuesday night – the very idea of Scotch. Their eyes squared with hers, emboldened by the clarity they had yet ever met; squinting, they tried to remember her but after a few seconds all they could do was look back at the husband, who had now reseated himself. “Okay, I guess wine sounds good.”

“Great!” he said and sprang from his seat again, making her smile somewhat in the old way, before medical school; perhaps she even let out a slight peep of a giggle. She had no course for intimidating him or turning their marriage into a true success or an actual failure, neither of which it could be classified at that moment. Things just happened. And as easily as both of them were bothered by his life and her especially of being the same small island off of it she had been when he had decided, it often passed as easily as the cork through the bottle’s top and not the needle’s eye, which it more properly resembled. He congratulated himself on what he considered small victories such as these, but his vision often failed him such that he was unable to see that she had only made a decision to call it off for a while. He proceeded to unconsciously gloat in his conversations about the hospital and the boy who would surely have died if not for the technique he had executed perfectly just that morning, which he recalled from an obscure journal article he had read and which had surrendered to his magnetic memory. Things that did not, could not, involve her, and these made up the blurred and windswept roadside she had been seeing all along. More he gloated, pushing his colleague into silence he mistook for respect and permission to continue the never-ending story of his worth. His duty was unclear, he thought and said in the same instant, and played tricks with his mind during the long days he spent at the hospital, at the humble service of a generic man. The wife sipped her wine and listened. Not to him, but to the voice inside her own thoughts, which she garnered without the need to verbalize immediately. She looked down on herself in the dining room among the three other people and imagined the scene just as it was, even with her husband talking. Except this time he was saying things which kept her interest and even flattered her; the colleague and his wife kept looking at her in amused adoration mixed with sensual envy as the husband shared brief tales not especially extraordinary except for the smile of believability through which he slipped them the words. She felt in love, not because she thought about it or was reminded of the fact by something he said to their guests, but simply in adjusting her eyes to where he sat. It aroused her, where he sat, the way he sat, and she knew the days and nights and places and unplaces where they had made love and loved each other almost as much as they did, sitting feet apart among two guests they had been obliged to entertain and nothing more. He made her feel the way only women at 24 or 28 know sex, just by the movements of his crossed leg, ever so perceptibly, back and forth. She could not wait, then, for the guests to complete their visit and bid an unacquainted farewell so she could take him by the trousers wherever she wanted as soon as the door slammed shut. It never took him long, she thought.

“Well, this has been wonderful,” the colleague began, interrupting more than he knew of the evening’s progress, of its host of events left incomplete, of its untold manners, of its ability to distract even itself. Things just happen, she considered as she re-entered the room consciously, slowly, reluctantly, with a pain immobile unless he would only, finally, press her into service.

© 2018 Alan Flurry