A somewhat cheeky line connects the many points along what I’ll call our Tech Fascination Capture. Describing that line can be tricky, but that’s what blogs are for, so here goes.

Interpretive problems that computers cannot solve, or rather those they can solve that aren’t the important ones, are at the center of a cognitive gap that is only increasing – and doing so fueled by our gaze and awe. We can’t seem to figure out why or how Russian troll farms might have swayed the most recent U.S. presidential election, if not others. Will artificial intelligence and the occupations lost to robots be good/a net value/desired? Self-driving cars – will we get there safely?

Much of this mystery is obscured by the need for a single answer to any one question, of course. But we are also frightened by the prospect of a single answer to multiple questions. This fear is a sort of disbelief itself, based on our own uncertainty about what we know from what we’ve learned, plus this more recent tendency to fall back on what everyone knows to be true. I’m actually unsure about the origin of that dynamic, though I am unafraid to speculate.

But, one thing is certain (and demanding of emphatic, if parenthetical, punctuation!): the answers lie in the questions themselves.

On social media misinformation, we don’t seem to want to contemplate the very top-level tradeoff: is the ability to connect with people worth the price of manipulation? That is, transmission of information and disinformation flow through the same tube – whether we believe one is sacred and the other profanely immoral or not is of not consequence whatsoever. There is one tube/portal; these are its uses; do you want to play?

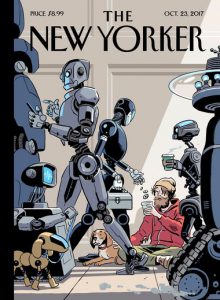

Will robots kick us to the curb and take our places? Who programs what robots can do? What will machine learning do about the should question? Is there such a thing as robot creativity, outside of MFA programs, that is?

Self-driving cars: so few startups and new products have anything to do with actual technology anymore that this one – which does – should (ha!) be attached with a free-rider proviso. The billions of dollars and pixels that accrue to its pursuit all ignore the same problem with driverless cars: unanticipated events. If a couple, holding hands, is jay walking and a young mother is in the crosswalk with her carriage on the same section of a street simultaneously, who gets run over? It all happens in an instant, plus bikes, buses, other cars (are there bad self-drivers?), weather, darkness… the idea that these variables can be solved is an answer to a solution, not a problem.

This is not to suggest understanding our capture is simple. But let’s think about it.