New Flagpole column up, and I’ve stepped away for the weekend to check out the view from one of the barrier islands. Back soon.

Omega-3s

This story about a single nutrient that turned early humans into civilized man, but which has been – thanks to to the industrialization of agriculture – systematically stripped from our diets over the last half century, has too many other parallels to let pass without noting.

Omega-3 molecules are a by-product of the happy meeting of sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide in the chloroplasts of terrestrial plants and marine algae. Not long ago, these fatty acids were an inescapable component of our diet. Back in the early 1900s—long before the arrival of bovine growth hormone and patented transgenic seeds–American family farms were perfect factories for producing omega-3s. Bucolic, sun-drenched pastures supported a complex array of grasses, and cattle used their sensitive tongues to pick and choose the ripest patches of clover, millet, and sweet grass; their rumens then turned the cellulose that humans can’t digest into foods that we can: milk, butter, cheese, and, eventually, beef, all of them rich in omega-3s. Cattle used to spend four to five carefree years grazing on grass, but now they are fattened on grain in feedlots and reach slaughter weight in about a year, all the while pumped full of antibiotics to fight off the diseases caused by the close quarters of factory farms.

When critics talk about so-called Frankenfoods and the insidiousness of genetically-modified organisms in our food supply, they’re not necessarily being Luddites or anti-biotechnology, even if that’s how large agricultural concerns define certain prohibitions on what they want to do. Any particular prohibition amounts to an utter and complete infringement of their rights to do whatever they want in the service of maximizing yields and profits. It’s much the same concept by which the insurance industry construes any steps to improve the healthcare system as socialized medicine – change one element to the way we do business and you’ll ruin the whole thing. I think that’s why the term ‘laissez faire’ has stuck in our business culture – it’s a euphemism for doing whatever you want – only you don’t have to say that and can hide behind a french idiom.

Because we’re always going to be finding out things like this, that were perpetrated unintentionally to dire effect at the behest of some enterprise(s) to maximize profits and which require mammoth efforts to even attempt to undo.

Maybe Il y devrait etre une nouvelle devise de puissance publique?

Sepia-toned future

For the six of you out there who don’t already read him, I link to today’s column from the shrill one – who now seems of the more sane among us. Go figure.

I would like to pick up on a few things he points out.

To be sure, the Obama administration is taking action to help the economy, but it’s trying to mitigate the slump, not end it. The stimulus bill, on the administration’s own estimates, will limit the rise in unemployment but fall far short of restoring full employment. The housing plan announced this week looks good in the sense that it will help many homeowners, but it won’t spur a new housing boom.

My first reaction to this is, we don’t need a new housing boom – that was one of the problems in the first place. But even this, as green as I always make it out to be, is itself a little too facile. What we don’t need is the same kind of crazy suburban housing boom, centered on and driven by the automobile in every way, and that is a non-trivial distinction if there ever was one. We do have to keep moving forward, a consequence of which is a growing population, one that needs housing. All the many things we talk about as far as energy efficiency, conservation, and lowered carbon footprint need to be incorporated in a kind of new housing boom. One that takes place nearer central cities, one that s accompanied by a boom in SUPERTRAINS and SUPERTRAIN TRACKS and SUPERTRAIN STATIONS, connecting this kind of housing boom to these smarter, much smarter goals for development being hatched on sites and across lecturns the nation over.

So… when Krugman also lays out some of the seeds of our recovery being planted…

Consider housing starts, which have fallen to their lowest level in 50 years. That’s bad news for the near term. It means that spending on construction will fall even more. But it also means that the supply of houses is lagging behind population growth, which will eventually prompt a housing revival.

Or consider the plunge in auto sales. Again, that’s bad news for the near term. But at current sales rates, as the finance blog Calculated Risk points out, it would take about 27 years to replace the existing stock of vehicles. Most cars will be junked long before that, either because they’ve worn out or because they’ve become obsolete, so we’re building up a pent-up demand for cars.

…These should only re-enforce the critical importance of putting these opportunities to work in the service of less waste, less energy, more walking, biking and mass transit. It could be a golden era – when our sepia-toned nostalgia for street car days of yore combine with the wizbang advantages of our high-tech faggery to give us copious amounts of actual time to piss away on stuff that matters. But it will require a major re-casting of all the tools we use to build houses and cars, including the nuts and bolts and screwguns and the materials they fasten but most importantly their designs and the regulations that guide them. Different requirements yield different outcomes, and that, my smiling-because-it’s-Friday friends, is what we’re after.

Book burning

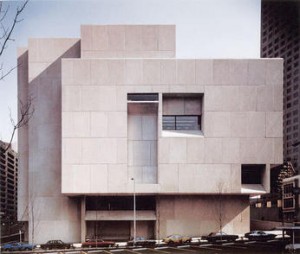

by any other name. A friend of mine wrote this article about another one of those, shall we say, constructive dilemmas: build a new-fangled structure in a newish city, wait thirty years until they want something else cutting edge (ouch!) and new, then watch as they decide what to do about the old building. In this case the old building is the final structure of Modernist master Marcel Breuer. Take it, JL:

Breuer’s design sits closely surrounded by other buildings where Peachtree Street, a principal artery, touches a remaining patch of narrow, 19th-century street grid, about a half mile southeast of the proposed Centennial Olympic Park site. If the building could be viewed whole, from a greater distance, its sculptural power might be more affecting. As it is, Pitts and others don’t get it. “From a design point of view, it probably means a lot to those in the field, but for the average citizen who sees it, it’s just not there,” he says. “It’s dark, it’s not friendly, it’s not inviting.” Isabelle Hyman, a Breuer scholar at New York University, acknowledges that “the concrete architecture of that period is disdained right now. It’s massive, heavy, bulky, weighty, and it’s not appreciated.” Still, she insists, “You just don’t get rid of a good building by a good architect because it’s out of style.” Pitts would prefer a building with of-the-moment transparency. “I envision glass and color and water and openness,” he says. But can a shiny new building attract patrons to the library, and visitors to Atlanta?

So… there’s a thread here, connecting what they’re contemplating doing with this building and what has saddled them with an urban landscape largely indistinguishable from that of Dallas or Indianapolis or Phoenix. Can anyone guess what it is?

For another thing, why not let the building stand as a marker for the question of why we designed and built structures like this once upon a time? Could be instructive.

And what do you know, there even could be a fiscal upside to preserving the structure, beyond its architectural merits.

Jon Buono, a preservation architect, makes a compelling pragmatic argument for saving the building. “I’m clearly interested in the artistic and cultural value of the library,” he says. “But as a civic booster, I’m even more concerned with recognizing the financial and material value of that public investment.” He calculates that the energy embodied in the library and required for its demolition equals a year’s electricity consumption by some 4,000 households.

Hmm. Preserve cultural heritage. Save the city some money. Conserve a non-trivial amount of energy. Does this compute? Or is it a plan written in a book, shelved in a library that’s become obsolete?

Book burning

by any other name. A friend of mine wrote this article about another one of those, shall we say, constructive dilemmas: build a new-fangled structure in a newish city, wait thirty years until they want something else cutting edge (ouch!) and new, then watch as they decide what to do about the old building. In this case the old building is the final structure of Modernist master Marcel Breuer. Take it, JL:

Breuer’s design sits closely surrounded by other buildings where Peachtree Street, a principal artery, touches a remaining patch of narrow, 19th-century street grid, about a half mile southeast of the proposed Centennial Olympic Park site. If the building could be viewed whole, from a greater distance, its sculptural power might be more affecting. As it is, Pitts and others don’t get it. “From a design point of view, it probably means a lot to those in the field, but for the average citizen who sees it, it’s just not there,” he says. “It’s dark, it’s not friendly, it’s not inviting.” Isabelle Hyman, a Breuer scholar at New York University, acknowledges that “the concrete architecture of that period is disdained right now. It’s massive, heavy, bulky, weighty, and it’s not appreciated.” Still, she insists, “You just don’t get rid of a good building by a good architect because it’s out of style.” Pitts would prefer a building with of-the-moment transparency. “I envision glass and color and water and openness,” he says. But can a shiny new building attract patrons to the library, and visitors to Atlanta?

So… there’s a thread here, connecting what they’re contemplating doing with this building and what has saddled them with an urban landscape largely indistinguishable from that of Dallas or Indianapolis or Phoenix. Can anyone guess what it is?

For another thing, why not let the building stand as a marker for the question of why we designed and built structures like this once upon a time? Could be instructive.

And what do you know, there even could be a fiscal upside to preserving the structure, beyond its architectural merits.

Jon Buono, a preservation architect, makes a compelling pragmatic argument for saving the building. “I’m clearly interested in the artistic and cultural value of the library,” he says. “But as a civic booster, I’m even more concerned with recognizing the financial and material value of that public investment.” He calculates that the energy embodied in the library and required for its demolition equals a year’s electricity consumption by some 4,000 households.

Hmm. Preserve cultural heritage. Save the city some money. Conserve a non-trivial amount of energy. Does this compute? Or is it a plan written in a book, shelved in a library that’s become obsolete?

means-as-medium

If we were truly the musical people that we think we are, there would be a growing discography based on the notion of a people who gorge themselves endlessly, yet are profoundly undernourished. But invariably, time from time someone leaves a door unlatched and a few bars or whole measure drifts out that is recognizable – how we have conditioned ourselves to think that we’re open to different ideas when that isn’t actually the case at all; that we’re already overtaxed with things to do and think about when we actually ask quite little of ourselves; how ‘the whole thing’ (whatever it is) is just too complicated when it’s often quite simple and only the onus of our choices which we find too troublesome to delve into.

The column this week touched on this idea in a very indirect way, via a coincidental example of an eco-themed art show. It’s greatly true that if you just keep in mind what it is that you’re doing, most situations tend to be navigable, that one included. In a timely NYT follow up (kidding), this article presents much the same take on a coincidental example, a review of a show by the recipient of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s Hugo Boss Prize.

When an artist uses her art to advance a political cause, how are we to judge the result? Should we evaluate the project by applying artistic standards or on the basis of its political or moral argument?

Consider Emily Jacir, who employs conventional devices of conceptualism and performance art to call attention to the plight of the Palestinian people.

This particular example of her work has a tertiary component that makes it even more suspect, but the point holds that even and especially with sympathetic subject matter, the basic premise of ‘art as means’ remains problematic.

However tragic and deplorable Mr. Zuaiter’s story may be, Ms. Jacir’s exhibition does not bring him to life sufficiently enough to elicit a strong emotional response. You may agree or disagree with her political goals and her use of the art exhibition system to further them. But the problem is with her unexceptional artistry, not her politics.

Just so.

The road to sustainability

tracks through the forest of stupid, veering off for extended moments in moronic triviality as we all behave like children for a little while longer. If you want to see the current dynamics of the debate over the financial crisis, gird your loins for this.

It’s amazing. On the one hand you have a couple sober realists, patiently speaking about the absolute necessity to massively de-leverage the insolvent banks… heaping ridicule on central bankers and others who didn’t see this coming but who remain in decision-making positions, insisting that banks must be nationalized. On the other, you have clowns asking for stock tips. There could be no more explicit description of the crisis itself than this display of inanity, which is at least representative if not the norm. When are we going to pull out of this? Like it’s just another slight downturn and not the collapse of the house of the mother of all pyramid schemes.

It’s a deep structural crisis. When Taleb tries to explain how executive compensation is tied to incentives that led to this mess in the first place, he’s met with demands to instead answer questions that are so far removed from the situation, they might as well be about the rock star status of Roubini and Taleb at the recent Davos summit.

Wait. That was what they were about. Nevermind.

Coffee Printer

Dost our eco-imaginations know no limits? Ladies and germs… the RITI Coffee Printer

In addition to ridding the printing process of the ink cartridge (its most environmentally un-friendly throw-out), the RITI printer also requires a bit of human action to get things going, which eliminates the need for any really significant power source. This last part of the idea seems a bit impractical, but after all that coffee you are drinking, maybe you need some exercise to burn off your excess energy!? Not a coffee drinker? No worries, it works just as well with tea.

Thanks, Amy.

My life is free

The title and the following are both from Henry Miller’s Remember to Remember, also known as vol. 2 of The Air-Conditioned Nightmare. This piece is called The Staff of Life.

Bread: Prime symbol. Try and find a good loaf. You can travel fifty thousand miles in America without once tasting a piece of good bread. Americans don’t care about good bread. They are dying on inanition but they go on eating bread without substance, bread without flavor, bread without vitamins, bread without life. Why? Because the very core of life is contaminated. If they knew what good bread was they would not have such wonderful machines on which they lavish all their time, energy and affection. A plate of false teeth means much more to an American than a loaf of good bread. Here is the sequence: poor bread, bad teeth, indigestion, constipation, halitosis, sexual starvation, disease and accidents, the operating table, artificial limbs, spectacles, baldness, kidney and bladder trouble, neurosis, psychosis, schizophrenia, war and famine. Start with the American loaf of bread so beautifully wrapped in cellophane and you end up on the scrap heap at forty-five. The only place to find a good loaf of bread is in the ghettos. Wherever there is a foreign quarter there is apt to be good bread. Wherever there is a Jewish grocer or delicatessen you are almost certain to find an excellent loaf of bread. The dark Russian bread, light in weight, found only rarely on this huge continent, is the best bread of all. No vitamins have been injected into it by laboratory specialists in conformance with the latest food regulations. The Russian just naturally likes good bread, because he also likes caviar and vodka and other good things. Americans are whiskey, gin and beer drinkers who long ago lost their taste for food. And losing that they have also lost their taste for life. For enjoyment. For good conversation. For everything worthwhile, to put it briefly.

What do I find wrong with America? Everything. I begin at the beginning, with the staff of life: bread. If the bread is bad the whole life is bad. Bad? Rotten, I should say. Like that piece of bread only twenty-four hours old which is good for nothing except to fill up a hole. God for target practice maybe. Or shuttlecock and duffle board. Even soaked in urine it is unpalatable; even perverts shun it. Yet millions are wasted advertising it. Who are the men engaged in this wasteful pursuit? Drunkards and failures for the most part. Men who have prostituted their talents in order to help further the decay and dissolution of our glorious Republic.

1947. You’ll have to scour a second-hand bookshop this weekend and get lucky for the rest. Or wait for periodic snippets here. As always, love your neighbor, read your Miller.

energy flows & waste streams

in communications, that is. Whether it’s their own supply chain and carbon footprint liabilities or those of thier clients, it seems that what green means has begun to have an impact on the advertising and marketing industry other than as a must-have trend. Here’s a video from Advertising Age, with Don Carli from the Institute for Sustainable Communication saying some smart things about… sustainability.

Sustainability as an ‘actual marketing strategy for growth’ is still a contradiction to my ears; but even as practiced by W*lmart, the savvy it portends will eventually boil down to a small playing field whereupon we witness, via pay-per-view, the cage match featuring a closed system vs. messaging. The closed system will prevail and then the whole cycle will begin again with the closed system as the premise – which will change the meaning of the terms actual, marketing, strategy and growth. Then things might get interesting.