Hurricane Ida grew quickly powerful after just a couple of days before roaring ashore and inundating people who have seen it before and likely will again:

By the time Hurricane Ida made landfall in Port Fourchon, La., on Sunday, it was the poster child for a climate change-driven disaster. The fast-growing, ferocious storm brought 150-mile-per-hour wind, torrential rain and seven feet of storm surge to the most vulnerable part of the U.S. coast. It rivals the most powerful storm ever to strike the state.

“This is exactly the kind of thing we’re going to have to get used to as the planet warms,” said Kerry Emanuel, an atmospheric scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology who studies the physics of hurricanes and their connection to the climate.

And the recent UN Climate report aside, scientists have been talking about this for years:

previous NASA-funded research by Theresa Andersen and J. Marshall Shepherd making the case that a “brown ocean effect” — evaporation from moist warm soils — can energize tropical systems.

A NASA news release on the 2013 research explained:

Before making landfall, tropical storms gather power from the warm waters of the ocean. Storms in the newly defined category derive their energy instead from the evaporation of abundant soil moisture – a phenomenon that Andersen and Shepherd call the “brown ocean.”

“The land essentially mimics the moisture-rich environment of the ocean, where the storm originated,” Andersen said.

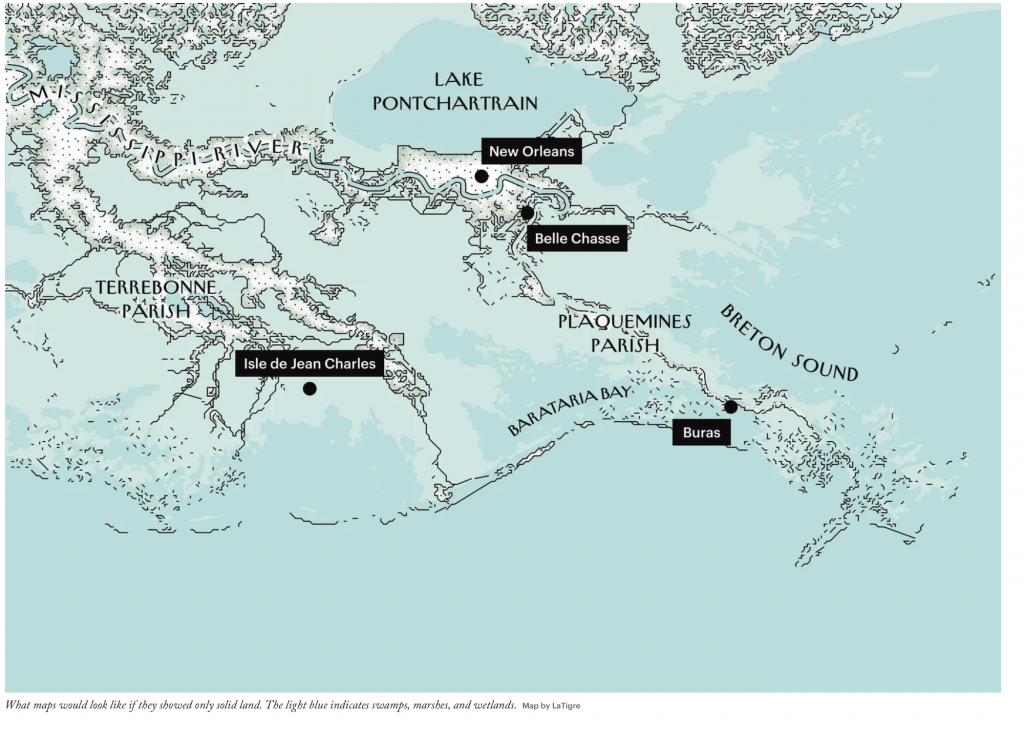

The map above says it all, and when we look at the photos from Sunday-Monday, listen to what we tell ourselves about what we see.

Image via the New Yorker